The Basics

One in nine Texas residents is not a U.S. citizen. Census

surveys don’t record which of those 2.9 million

non-citizen residents are here lawfully, but the best

estimates are that 60 percent or more lack legal status.

Of the 5 million uninsured Texans in 2014, about 1.6

million were non-U.S. citizens. Non-citizens—even

those who are lawfully present—are not eligible for

public health insurance on the same terms as U.S.

citizens, and options for undocumented residents are

especially limited.

The 2014 roll out of the Aordable Care Act’s (ACA) new

private and public health coverage options brought

new rules and opportunities for non-US citizens. But

the law also had unintended consequences, and

barriers to care for immigrants remain signicant—

especially here in Texas. Undocumented residents are

excluded from all formal public insurance programs

(except for payment of some emergency services

in Medicaid), and legal residents face signicant

technological and legal barriers related to both public

coverage and private insurance in the new Marketplace

established by the ACA.

To reduce the confusion about which non-U.S. citizens

can access what healthcare and which programs, we

have prepared the table below. Read more about the

law, policy and history in the sections that follow.

Immigrants’ Access to Health Care in Texas:

An Updated Landscape

by Anne Dunkelberg

B

arriers to health care facing long-term resident non-citizens aect every Texan. The hospitals, clinics,

and other health care systems we all share, rely on, and nance through our taxes and insurance

premiums can only be eective if they address the health needs of all Texans, from controlling

communicable diseases to prenatal care and trauma care. Millions of U.S. citizen Texans are uninsured (the

highest uninsured number and rate in the U.S.), and our state’s large immigrant population faces all the same

barriers to care as U.S. citizens, plus an additional complex list of exclusions. The eects reach far beyond any

individual immigrant. One-third of Texas children have a foreign-born parent, and foreign-born workers and

small employers in Texas make hefty contributions to our state economy (see: Immigrants Drive the Texas

Economy: Economic Benets of Immigrants to Texas). When individual immigrants are disenfranchised from

access to health care it can aect whole families, and the health and prosperity of the communities in which

they live, work, study and worship. Like any other uninsured Texan, immigrants who delay getting care too

often end up needing costly emergency care on the local taxpayer’s tab.

October 2016

In This Report

• Texas Choices: Immigrants and Public

Health Care Programs

• Non-Citizens in Texas: A look at the

Numbers

• Helpful Immigration Terms

• Table: Immigrants’ Access to Health Care

in Texas, 2014

• Why Fears of Immigration Consequences

Cause Some to Avoid Health Care

• ACA Extends Aordable Marketplace

Coverage to Lawfully Present

• Undocumented Residents: Federal and

Texas Policy

• Rights and Rules When Mixed-

Immigration Families Apply for Health

Care

• ACA Marketplace: Coverage and

Challenges for Mixed-Immigration

Families

• Recap: Focus on Gaps in Access to Care

for Immigrants in Texas

• APPENDIX: Immigrants and Health Care:

Federal Policy Basics

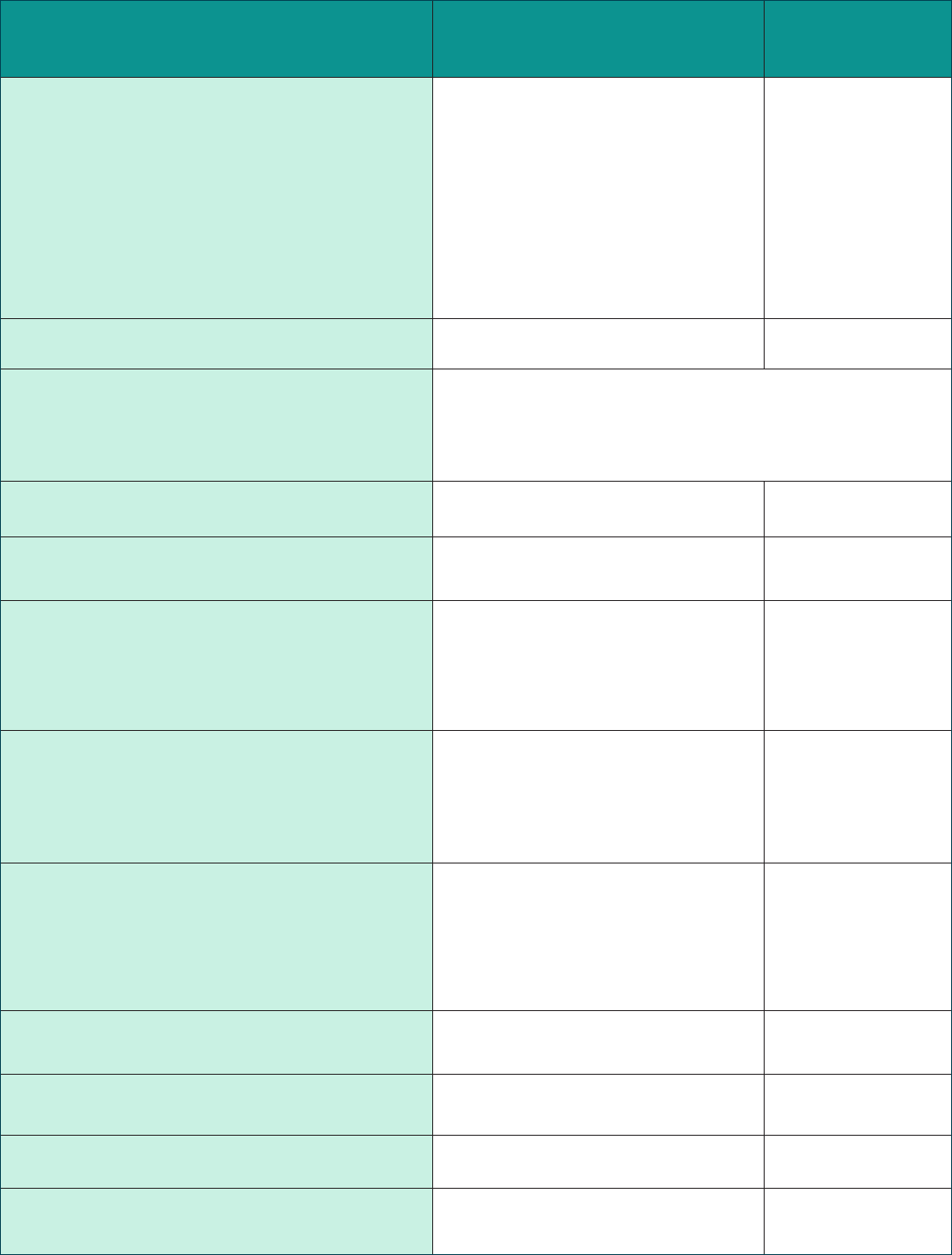

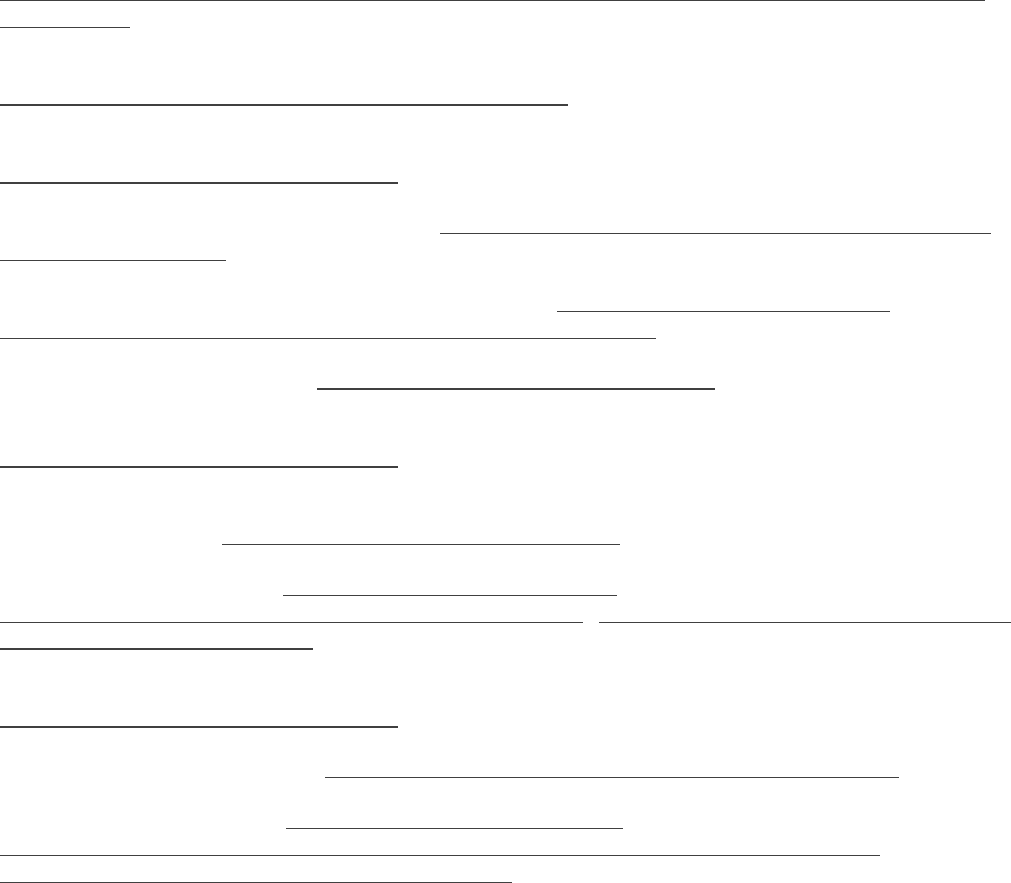

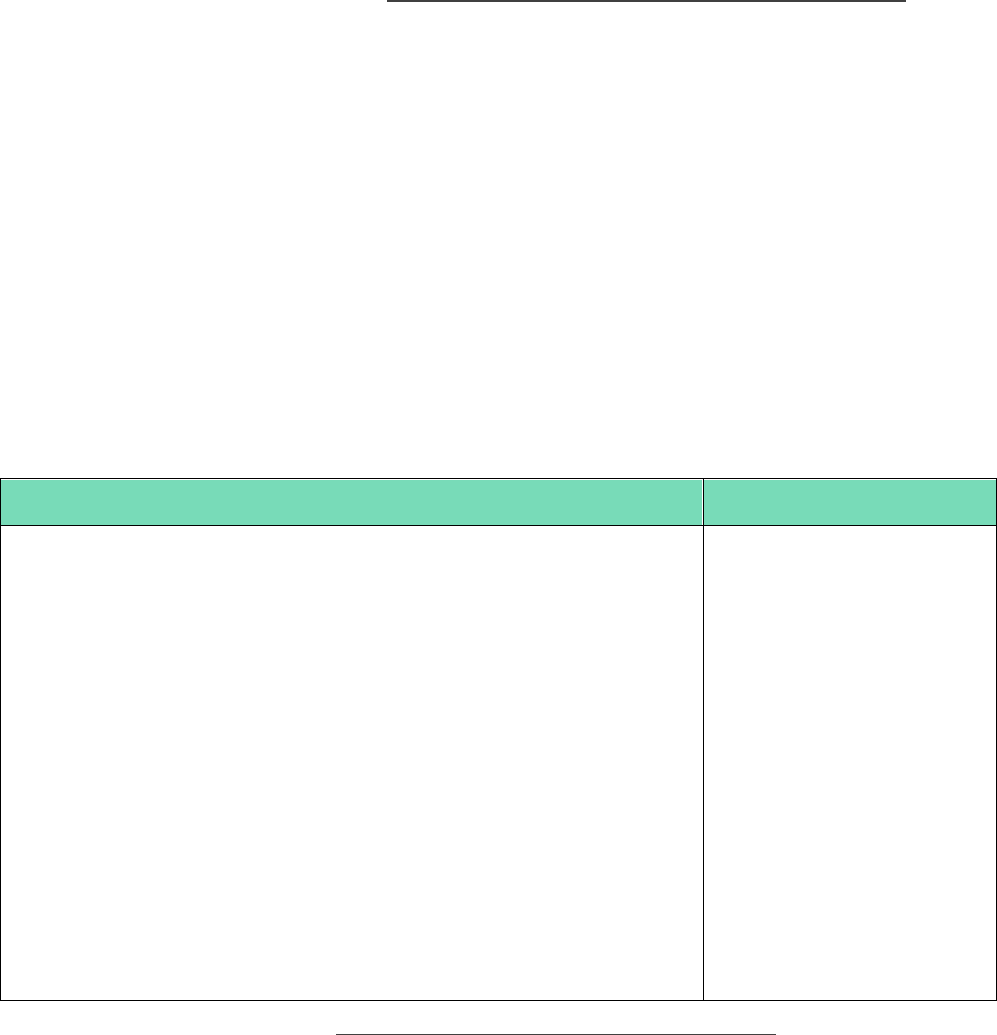

Table 1: Immigrants’ Access to Health Care in Texas, 2016

Health Care Program or Service

Lawfully Present

Immigrants

Undocumented

Immigrants

Medicaid-Adults 19 and older

NO for most immigrants who came

to U.S. on or after 8/22/1996

YES, for immigrants before

8/22/1996, but limited to same

categories as U.S. citizens (very few

parents qualify, and no adults without

dependent children unless pregnant,

senior, or disabled)

NO

Medicaid-Children under age 19 YES NO

“Emergency Medicaid”- pays care providers

for emergency care only (not full coverage)

YES, but only ER bills for individuals who, except for immigration status,

meet all the same strict TX Medicaid limits that apply to U.S. citizen

adults (very few parents qualify, and no adults without dependent children

unless pregnant, senior, or disabled)

CHIP-Children under age 19 YES NO

CHIP Perinatal Program-prenatal, delivery,

and postpartum care

YES YES

Refugee Medical Assistance

Medical assistance to refugees for up to 8 months from

the individual’s legal date of entry (those who apply

after their legal date of entry month receive less than 8

months of RMA coverage).

YES

Must have a U.S. CIS

veried refugee status

NO

Programs using federal health care block

grant funds (includes those run by state, county or

city): Examples: mental health, maternal and child health,

family planning, communicable diseases, immunization

YES YES

Programs providing health services

necessary to protect life or safety, includes

those using federal, state or local funds. Emergency

medical, food, or shelter, mental health crisis, domestic

violence, crime victim assistance, disaster relief

YES YES

County Hospital or Health Districts and

Indigent Care Programs

YES VARIES by County

Marketplace Insurance Coverage, with

subsidies

YES NO

Marketplace Insurance Coverage, no subsidy YES NO

Insurance purchase outside Marketplace,

no subsidy

YES YES

W

ith over 4.6 million uninsured Texans in

2015, substantial gaps in access to health

care will remain a problem for many Texans

in the near term, despite the important gains and

new options provided by the ACA. Listed below is a

partial inventory of notable holes in the Texas health

care safety net for non-U.S. citizen residents.

Undocumented. The greatest access gaps for non-

citizens aect Texans without legal immigration

status. Barred from Medicaid, CHIP, and the

Marketplace and its subsidies, private health

coverage is available only to undocumented

individuals who have adequate income to

purchase a policy at full price, without a subsidy.

Undocumented residents can look to Federally

Qualied Health Centers, some (but not all) urban

hospital/health districts, and independent charity

clinics for care, meaning that access to aordable

care is highly variable depending on where an

immigrant lives in Texas.

Lawfully present: Immigrants who are lawfully

present in the U.S. face certain barriers that are

specic to their non-citizen status, as well as some of

the same barriers aecting U.S. citizens.

● The Coverage Gap traps some lawfully present,

including refugees and asylum seekers. Most

lawfully present individuals with incomes below

100 percent of the FPL can qualify for subsidies in

the ACA Marketplace. However, certain lawfully

present immigrants are caught in the Coverage

Gap in states like Texas that have not accepted

federal ACA funds to extend Medicaid to adults

who earn less than 138 percent of the FPL. So

the categories of legal immigrants that Congress

intended in 1996 to have access to Medicaid

and CHIP, actually are the very ones who are left

without coverage options in Texas and other

states that have not expanded Medicaid.

● Texas law excludes most lawfully present

immigrant adults from Medicaid. The state

legislature would have to authorize a change to

this state policy (adopted in 1999) in order for a

Texas solution to insure low-income Texans in

the Coverage Gap to also benet lawfully present

adults below the poverty line.

● Technical Marketplace application processing

issues for individuals with immigration

documents, as well as for mixed-status families

have delayed coverage and discouraged eligible

Texans from completing enrollment. Improved

Marketplace performance during the second

and third open enrollment period appears

to be improving enrollment rates but further

improvement is still needed.

● The “family glitch” aects both lawfully present

immigrants and U.S. citizens. These families

may not qualify for premium subsidies in the

Marketplace , and face either paying full price and

an unlimited, unaordable percentage of their

incomes for job-based or Marketplace insurance

premiums, or remaining uninsured.

● Aordability issues occur even for families that

have access to premium subsidies and out-of-

pocket help in the Marketplace. Those below

poverty may have a hard time aording 2

percent of income in premiums with additional

copayments and deductibles. Families at any

income level who experience high health care

needs may face spending up to 20 percent of

income before deductibles and out-of-pocket

caps kick in.

● Separated, but not divorced, parents may not

have access to Marketplace subsidies because

of tax ling status or lack of access to income

information on the absent spouse.

● Hard-to-verify incomes. The income verication

systems that the Marketplace and state Medicaid-

CHIP programs rely on can work well for those

with steady employment and predictable hours

and wages. They are less helpful for those working

irregular hours, multiple jobs, or being paid cash

or by hand-written check. Advocates will need to

monitor the systems to identify and try to reduce

any barriers to enrollment, renewal, or qualifying

for premium subsidies that may result from

the additional documentation families in these

situations may have to produce on an ongoing

basis.

Executive Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations for Texas

How to use this report to protect access to care in your community

Why This Report?

This report provides an updated overview of federal and state laws and rules governing access to health care in Texas

for non-U.S. citizens, and points out how local practices vary around the state. With a new presidential administration

beginning in January 2017, changes to weaken protections in federal laws and rules could be proposed in the near future.

Attempts to make health care less accessible to non-U.S. citizens are on the rise. In the past, health care stakeholders in

Texas avoided direct talk about the programs and services available to non-citizens—even those lawfully present—in

hopes that silence would reduce attacks on immigrants’ health care access. At CPPP, we believe that given the increased

frequency of attacks on access, silence is no longer serving that end. Health care providers, community advocates,

congregations, and concerned citizens all need to be armed with the facts about federal, state, and local laws and the

rights of immigrants. Only armed with this information can we ensure that laws are followed and rights are protected.

CPPP is available to help educate organizations and community members, and to hear reports from those who observe

violations of law or policy, or need help understanding if a violation has occurred. Information on how to contact us is at the

end of this report.

Recommendations to Improve Health Care

Access and Outcomes

Federal law, Texas law and the state constitution combine

to make Texas cities, counties, and hospitals the providers

and funders of last resort for all of the uninsured. U.S.

and Texas law allow federal and state government to

reject the health costs of uninsured immigrants—lawfully

present and undocumented alike—and shift them to

local governments and health care providers. In this way,

Texas’ policy decisions to turn down available federal

support for the uninsured take a toll on local taxpayers,

and on all the other services communities need to fund.

CPPP recommends that Texas make the following three

key policy changes to increase federal funding for

coverage and care of immigrants:

1. Providing Medicaid Maternity benets to lawfully

present immigrant women. Texas should provide

comprehensive pregnancy benets on par with those

of U.S. citizens. Today, even legal permanent residents

are treated the same as undocumented mothers.

2. Closing the Texas Coverage Gap, and insuring all

citizens 19-64 up to 138 percent of the federal

poverty line ($27,724 for a family of 3). This step

would do even more than #1 for maternal health, by

allowing women access to medical homes before

conception for healthier pregnancies, continuing their

care after birth to screen for and treat chronic medical

conditions, and thereby improving health for any

future pregnancies. This improved care will be gained

equally if accomplished via an 1115 “red state waiver”

conservative alternative.

Closing the Gap will also eliminate today’s perverse

policy which denies access to coverage to immigrants

Congress intended to protect: e.g., active-duty

military and veterans, victims of human tracking,

and refugees. Step #2 will also dramatically improve

payments to hospitals and doctors for emergency care

to uninsured undocumented residents.

3. Providing Medicaid benets to lawfully present

immigrants aged 19 and older. Lawmakers should

also reverse the Texas law that now excludes these

adults, in order to maximize the reduction in uninsured

lawfully present Texans and the relief for local

governments that closing the Coverage Gap would

bring. Texas Medicaid today covers very few U.S. citizen

parents and adults under current policy: e.g., 3 million

children are enrolled, but only 150,000 of their parents.

Unless Texas begins providing coverage options for

U.S. citizen parents and other adults living in poverty,

reversing Texas’ ban on Medicaid for lawfully present

immigrant adults will have limited eect.

Of course, the steps described above do not fully address

the barriers to care for undocumented residents and the

costs of their care born by local governments and care

providers. Texas should take the lead among the states,

squarely face the realities and negative consequences

of these barriers for our communities, and develop a

proactive strategy to improve systems and nancing of

care for the undocumented uninsured.

CENTER FOR PUBLIC POLICY PRIORITIES • CPPP.org • 5123200222

CPPP_TX

BetterTexasBlog.org BetterTexas

Immigrants’ Access to Health Care in Texas: An Updated Landscape

5

Texas’ Choices: Legal Immigrants and Public Health Care Programs

See Appendix and Resources for more detailed federal policy background.

1997: Texas Denies Medicaid to Most Recent Legal Immigrants.

The Texas Legislature opted in 1997 to continue providing Medicaid to “qualified immigrants” (see Helpful

Immigration Terms box, p. 3, and Appendix) who came to the U.S. before the 1996 federal welfare law known as

the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reform Act (PRWORA, 8/22/1996). But the state Legislature

decided to exclude qualified immigrants who came to the U.S. after that date, even when they have been in the

U.S. for five years and qualify for federal Medicaid funding. (In 2001, the Legislature passed an omnibus

Medicaid bill that would have reversed that decision and allowed post-1996 qualified immigrants to qualify for

Texas Medicaid, but that bill was vetoed by the Governor).

Non-Citizens in Texas: A Look at the Numbers

THE BIG PICTURE: U.S. Census estimates non-U.S. citizens made up 2.9 million of the 26.9 million Texans in 2014

(Census, American Community Survey).

U.S. Census does not determine which non-citizens are lawfully present and which are not.

68% of foreign-born Texans (including naturalized U.S. citizens) are of Latin American origin, 18% Asian. (Migration

Policy Institute (MPI), 2014.)

UNDOCUMENTED: Pew Hispanic Center estimates Texas was home to 1.7 million undocumented immigrants in 2012;

MPI estimates about 1.5 million for 2014.

The U.S. unauthorized immigrant population peaked in 2007 at about 12.2 million.

Since 2008 the national total has declined by about 1 million and more undocumented immigrants have left the

state than have moved here, due to the global recession, increased border security, and greater risk to migrants

from criminals.

The drop was due mostly to reduced immigration from Mexico.

Additional sources: Pew Hispanic Center, Statistical Portrait of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States,

September 2015; 5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S., November 2015.

CHILDREN:

Though only 4% of Texas children are themselves foreign-born, in 2014 2.4 million Texas children (one-third of Texas

children) had a foreign-born parent (Annie E Casey Foundation Kids Count project estimates).

o Half of these children are in families in which neither parent is a U.S. citizen (includes both lawfully present

and undocumented parents).

o Of Texas children in these mixed-status families, 33% live below the poverty line ($20,160 for a family of 3),

compared with 25% of all children.

The Migration Policy Institute estimates that 45% of all low-income Texas children (those with family income below

200% FPL, which is the upper limit for the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), $40,320 for a family of 3)

have at least one foreign-born parent.

The Texas Medicaid program reports it covered costs for 213,253 Texas births in 2013.

o That year, Texas Medicaid paid for deliveries for about 159,000 U.S. citizen mothers.

o About 26% of Texas Medicaid births in 2013 were to non-U.S citizen mothers (about 55,000, includes both

lawfully present and undocumented mothers), representing about 15% of all Texas births that year.

6

1999: Texas includes Legal Immigrant Children in CHIP

The option for each state to create a Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was established by Congress in

1997 when the Texas Legislature was not in session, and the Legislature enacted CHIP coverage in 1999 in its next

regular session. The federal law required Texas to include qualified immigrant children who have been in the U.S.

for at least five years in our separate (non-Medicaid) CHIP program, but provided no federal funding for those

children during their first five years in this country. The Texas Legislature opted to use 100 percent state funds to

cover qualified immigrant children in CHIP during their first five years in the U.S. when no federal match was

available, convinced that promoting early intervention and a regular source of medical and dental care for

children would be cost-effective in the long run.

Helpful Immigration Terms

“Alien” is a term used in many laws to refer to noncitizens (both lawfully present and undocumented).

“Undocumented” Immigrants include 2 major groups, people who:

Entered Without Inspection, or “EWIs”

Overstayed their immigrant or nonimmigrant visas; these make up 25-40 percent of all undocumented immigrants

Other terms you may see: “not lawfully present,” “illegal aliens” (the latter term is not preferred or used in this report)

“Legal Immigrant” – not a real term in law, but still is commonly used. There are many different lawful immigration

statuses:

Some are permanent or long-term statuses; that is, the immigrant can reside in the U.S. indefinitely. Includes

Lawful permanent residents (LPRs), refugees, and asylum seekers (“asylees”).

Others are temporary, or transitional statuses, which may be indefinite in length (for example, the spouse, child

or fiancée of a U.S. citizen waiting to get LPR status may have a “K” Visa), or they may be required to get approval

for renewal of status at regular intervals (e.g., “Temporary Protected Status”).

Most LPRs immigrated through a family-based immigrant visa petition.

All lawfully present immigrants are not treated equally with regard to access to health care.

NOTE: “qualified” and “lawfully present” immigrants have different specific meanings in law and policy. They are

italicized in this report when they refer to a specific legal or regulatory definition.

“Qualified” Immigrants

A specific group of immigration statuses that was designated in the 1996 federal welfare law for the purpose of

establishing new restrictions on eligibility for public benefits. (See appendix for detail)

“Lawfully Present” immigrants

Federal categorization of immigrants who are potentially eligible for Medicaid and CHIP under the state option to

cover children and pregnant women established in 2009 federal law (under the Children's Health Insurance

Program Reauthorization Act, CHIPRA), and for Marketplace insurance under the Affordable Care Act. It includes

almost all legal statuses, including non-immigrants with valid visas. (See appendix for detail)

The words “lawfully present” are sometimes also used to refer generically to non-U.S. citizens who are not

unauthorized. In this report we italicize lawfully present when it is used to refer to the specific grouping of lawful

statuses established in federal law and policy related to access to health care and insurance programs.

“Immigrant” versus “Nonimmigrant” visas

“Immigrant” statuses include people seeking long-term or permanent residence.

Tourists, students, people conducting business, temporary employees, or those traveling to the U.S. to receive

medical care are the primary examples of “non-immigrant” status.

7

By 1999, federal legislation had already been introduced in response to PRWORA to give states the option to

eliminate the five-year bar from Medicaid and CHIP for immigrant children and pregnant women. The authors of

Texas’ CHIP law therefore included a “trigger” in Texas law directing the program to accept federal funding for

immigrant children in their first five years, should Congress ever adopt that bill and make that option available.

Today: Where Medicaid and CHIP stand in Texas

Qualified immigrants who entered the U.S. before August 22, 1996 may participate in Medicaid on the

same terms as U.S. citizens.

Most qualified immigrants ages 19 and older who entered the U.S. on or after August 22, 1996 are not able

to access Texas Medicaid (see Appendix for exceptions).

o Texas is one of just six states that exclude qualified immigrant adults from Medicaid if they came to

the U.S. after the 1996 federal welfare law took effect. (Alabama, Mississippi, North Dakota, Virginia,

and Wyoming are the others).

o This Texas policy means Medicaid maternity coverage is not available to qualified immigrant women.

Instead, these women are treated the same as undocumented immigrant women. They can

participate in the “CHIP Perinatal” program, which provides prenatal visits and limited postpartum

care, and “Emergency Medicaid” (more below) will pay the bill for labor and delivery. They cannot get

coverage with more comprehensive pre-conception care or postpartum health care.

Texas also has extremely limited Medicaid coverage for adult U.S. citizens, because the state has not yet

accepted the federal funds available under the ACA to cover most U.S. citizen adults with incomes below 138

percent of the federal poverty income level ($27,821 for a family of 3). But even with the current limits in

place for U.S. citizen adults, tens of thousands of pregnant women and thousands of parents could gain

comprehensive health benefits if Texas stopped excluding qualified immigrant adults who came here on or

after August 22, 1996 from Medicaid coverage.

If the state moves forward to accept the coverage of all U.S. citizen adults up to 138 percent FPL, taking the

additional step of ending the exclusion of adult qualified immigrants from Texas Medicaid would be needed,

to provide affordable coverage to legal immigrant adults in that income group.

Lawfully present immigrants 18 and younger may participate in Texas Children’s Medicaid and CHIP on the

same terms as U.S. citizen children. When Texas CHIP was launched in 2000, all qualified immigrant children

with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty income were enrolled in CHIP (not Medicaid). When

Congress passed the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act in 2009 (CHIPRA), it created the

option for states to get federal matching funds for children and pregnant women without a 5-year wait. As

directed by Texas’ 1999 CHIP law, Texas Medicaid and CHIP then implemented the option to accept the

federal funds for children in Medicaid and CHIP (but not for pregnant women), without a 5-year wait.

Congressional CHIP Reauthorization in 2009 also extended the categories of eligible immigrant children to the

broader group of lawfully present children (see Appendix). Lawfully present immigrant children today are

covered in Texas Medicaid and CHIP according to the same income guidelines as U.S. citizen children.

8

Importantly, under the CHIP Reauthorization, the U.S. “sponsors” of immigrant children and pregnant women

covered in Medicaid or CHIP are not liable for repayment of health care costs, and a sponsor’s income is not

counted as part of the immigrant’s income for eligibility purposes (see below, Sponsor Income and Liability,

and Fears of Immigration Consequences).

CHIP Perinatal Program. Texas authorized the CHIP Perinatal program in 2005 using CHIP funding to provide

prenatal visits and limited postpartum care to both lawfully present and undocumented immigrant mothers

with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line ($40,320 for a family of three), because they are

excluded from Medicaid Maternity coverage. Emergency Medicaid (more below) pays the bill for labor and

delivery. (CHIP perinatal also is available to U.S. citizen mothers with incomes between 185-200 percent of the

FPL).

State and Local Health Care Programs. Federal law and regulations provide access to all other health care

programs—such as maternity care, mental health, immunizations, disease control—for qualified immigrants

(see Appendix). Importantly, state and local health programs cannot add their own immigrant restrictions to

any public health programs that use those unrestricted federal funds. Texas operates relatively few public

health programs that do not mix federal funds with state dollars.

The most common locally funded and operated health care programs in Texas are hospital and health district-

funded medical assistance programs typically found in the largest urban counties, and the County Indigent

Health Care programs in most smaller-population counties without hospital or health districts. Texas Hospital

Districts do have an obligation under both state law and the Texas Constitution to serve all needy residents.

As a general rule, local health care programs have not restricted access by qualified immigrants.

Individuals with “non-immigrant” status (such as student, tourist, and employment visa holders) are required

to prove that they are residents in some Texas localities in order to use these health care programs. What is

accepted to prove residency differs from place to place, but in some locales includes rent receipts or utility

bills, to establish some intent to reside in the community. Federal rules for Medicaid and the Health insurance

Marketplace prohibit state Medicaid programs or Marketplaces from defining a person to be a non-resident

based strictly on their immigration status or type of visa.

i

The federal rules represent a fairly new best

practice, and may influence Texas counties to update their policies in places that reportedly still assign non-

resident status to immigrants based solely on their visa type.

Sponsors’ Income and Liability. Many Lawful Permanent Residents (often called “green card” holders) are

sponsored by a relative or others who promise to help provide for the new immigrant’s needs. In 2011, the

state Legislature adopted a new law allowing county health care programs to count (“deem”) the income and

resources of immigrants’ sponsors when determining if an immigrant is eligible for a Hospital District or

County Indigent Health Care program. The same legislation also gave those programs the option to recover

costs of care from the sponsors, and directed the Texas Medicaid program to do the same if cost effective. Of

course, counting the income of a separate household as though it were available to the immigrant reduces

the ability of an immigrant family to qualify for care. It’s not known how common the practice is in Texas,

since at this time it appears that no state entity maintains a centralized record of the policies adopted by local

governments.

9

ACA Extends Affordable Marketplace Coverage to those Lawfully Present

When the ACA was passed in 2010, it made the same group of “lawfully present” immigrants defined in the 2009

CHIP Reauthorization eligible to participate in the new health insurance Marketplace in 2014. Those with incomes

below four times the federal poverty line income ($80,640 for a family of three in 2016) can qualify for reduced-

cost insurance through lower premiums (subsidized with “premium tax credits”) and reduced out-of-pocket costs

(“cost-sharing reductions”) for families with incomes below 250 percent of the federal poverty line. Just like U.S.

citizens, lawfully present immigrants who are offered “affordable” job-based coverage do not have access to

marketplace subsidies (more later, see “Family Glitch”).

Why Fears of Immigration Consequences Cause Some to Avoid Health Care

Fear of being Labeled a “Public Charge”

Some immigrants fear that using publicly sponsored health care or subsidies will prevent them from getting legal

status or citizenship. Federal policy in place since 1999 has tried to reassure non-citizens that use of health care by

eligible people will not create barriers to immigration or citizenship, but confusion and fear remain among both

undocumented and lawfully present immigrants.

The only way health care use can prevent a green card holder from becoming a citizen is if he or she committed

fraud to get those benefits (for example, misrepresented his or her income, state residence or immigration status).

Sponsor “deeming” and liability

Many Lawful Permanent Residents (sometimes called “green card” holders) are sponsored by a relative or others who

promise to provide for the new immigrant’s needs. In some situations, the sponsor’s income can be counted

(“deemed”) as if available to the sponsored person in determining eligibility for health care services. And though

asking sponsors to repay the costs of care (“liability”) provided to those they sponsor is almost unheard of, it is

technically possible under the law in some cases and thus creates a barrier for some immigrants. Care for children in

Texas CHIP or Medicaid is exempt from sponsor deeming and liability.

Reporting to the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS, formerly INS)

Medicaid, CHIP, other health programs and health care providers are not required to report all undocumented

persons to immigration authorities. Indeed the Department of Homeland Security has confirmed that it will not use

information provided by health care applicants for immigration enforcement purposes. Reporting to USCIS can occur

in cases of fraud, but is not done simply based on a household including a person with undocumented status. Still,

immigration officials have on occasions been known to seek out immigrants in health care settings, which can create

long-lasting fears spread by word of mouth, and make immigrants reluctant to get necessary care.

Congress intended for all U.S. citizens aged 19 to 64 and with incomes up to 138 percent FPL to qualify for

Medicaid in every state. The ACA’s Marketplace subsidy provisions limited premium assistance to U.S. citizens at

or above the poverty line (100 percent FPL), on the assumption that all U.S. citizens below that income would

qualify for Medicaid. But after the U.S. Supreme Court removed any penalty for states failing to implement the

expanded Medicaid for adults, a number of states have left their uninsured U.S. citizen adults below poverty who

don’t qualify for Medicaid without an affordable option. As of March 2016, 19 states (including Texas) had not yet

taken action to cover the poorest uninsured in this “Coverage Gap,” though several of those states have active

debate underway on the topic. The Supreme Court decision only eliminated fiscal penalties for states that did not

expand Medicaid coverage to 138 percent of FPL, but made no other changes to the ACA. Thus, the law still only

allows subsidies to U.S. citizens above the poverty line, even in states with no Medicaid coverage assistance for

adults in families with poverty-level incomes.

10

Most Lawfully Present Immigrants Escape the Coverage Gap

Congress intended for lawfully present immigrants, including qualified immigrants in the “5-year bar,” to have

access to affordable healthcare, so the ACA allowed these lawfully present immigrants below the poverty line (100

percent FPL, $20,090 for a family of three) to qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace. Under the ACA, a lawfully

present immigrant below poverty can qualify for Marketplace subsidies if they were excluded from Medicaid

because of immigration status.

Texas excludes most qualified and lawfully present immigrant adults (age 19 and older) from Medicaid (exceptions

include pre-1996 immigrants and several categories of federally mandated exceptions). Because of this exclusion

on the basis of immigration status, most qualified immigrant adults in Texas with incomes below 400 percent

FPL—including those with incomes under the poverty line—can qualify for financial help in the ACA Marketplace.

Access to Marketplace coverage, including premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions, is not subject to a

five-year waiting period.

The unintended result of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Medicaid is that in non-expansion

states, most lawfully present immigrants with incomes below the poverty line can gain

access to the Marketplace premium and cost-sharing subsidies, while their U.S. citizen

neighbors with the same income cannot. In fact, when Arizona’s Governor adopted Medicaid

Expansion, she cited the desire to eliminate this inequity as one of her reasons.

….But Some Lawfully Present do Fall Into Coverage Gap

The ACA’s exception that allows lawfully present immigrants below 100 percent FPL access to subsidies (that is,

even though U.S. citizens at that income are denied) applies in cases where the immigrant is denied Medicaid on

the basis of immigration status. As described in the appendix, access to Medicaid for certain qualified

immigrants—e.g., active military, refugees and people granted asylum during their first 7 years in the U.S., and

survivors of human trafficking—was protected in 1996 law, so they are treated like U.S. citizens for purposes of

Medicaid eligibility.

Ironically, because these individuals are not excluded from Texas Medicaid based on their immigration status, but

instead are only excluded because of Texas’ failure to date to establish Medicaid coverage for adults, they fall into

the Coverage Gap along with their U.S. citizen peers.

So the categories of legal immigrants that Congress intended in 1996 to have access to

Medicaid and CHIP, actually are the very ones who are left without coverage options in

Texas and other states that have not expanded Medicaid.

Rights and Rules When Mixed-Status Families Apply for Health Care

• Only the individual applicant's immigration status is relevant to his eligibility; for example, a parent's

immigration status does not affect a U.S. citizen child's eligibility for public benefits.

• Medicaid, CHIP, and the Marketplace do not, and may not, require either a Social Security Number or

immigration status information from parents who are applying for health care for their children, and not

for themselves—or from any other non-applicant household members.

• Medicaid, CHIP and the Marketplace will ask parents who do have a valid Social Security Number to

voluntarily provide it. Individuals should provide only valid Social Security numbers that were issued to

them by the Social Security Administration.

• A U.S. citizen or lawfully present person who is applying for coverage for themselves can be required to

have—or to apply for—a Social Security Number to get Medicaid or CHIP.

11

Undocumented Residents

Undocumented Residents and Health Care Access: Federal Policy Basics

Undocumented residents have never qualified for Medicare, Medicaid, or CHIP enrollment with full benefits.

However, Medicaid does include an important program that pays emergency medical bills of some immigrants

who are excluded from full coverage. Most other non-entitlement federally funded health care programs—like

immunization, mental health, prenatal care, and community health centers—are by law open to all who qualify

based on need, and without restrictions based on immigration status. Federal CHIP regulations allow states to

fund prenatal care for immigrant mothers excluded from Medicaid themselves, but whose children when born will

be CHIP- or Medicaid-eligible as U.S. citizens.

Emergency Medicaid. The slightly misleading name of this program results in some common misunderstandings

about what it does, and for whom. Federal law requires that all state Medicaid programs pay Medicaid care

providers for emergency medical care they provide to people who meet all the state’s eligibility requirements

except for citizenship or immigration status.

Key facts often misunderstood include:

Only bills for patients who meet all of Medicaid’s same income and other requirements that would apply

to a U.S. citizen (that is, people who qualify in every other way but for immigration status) can be paid, so

many emergency care bills for undocumented immigrants do not qualify for coverage.

Covered services typically are limited to services provided in the Emergency Department for medical

emergencies, with the important addition that covered emergency care services are specifically defined in

federal law to include labor and delivery.

As a general rule, states do not enroll undocumented residents or issue Medicaid cards for Emergency

Medicaid. Instead, patients apply through their health care providers for their emergency care bills to be

paid.

Emergency care for lawfully present immigrants is also reimbursed by this program in Texas, and the

other five states that exclude legal immigrants from Medicaid eligibility.

Despite its broad-sounding name, the Emergency Medicaid program does not cover any emergency

medical bills for uninsured U.S. citizens; it is only for those bills of non-citizens excluded from Medicaid.

Other Federal Health Care Block Grants are Generally Not Restricted. The 1996 welfare and immigration laws

established new guidelines for undocumented residents’ access to federally funded health care from other

programs. A special set of guidelines applies to the non-entitlement federal health and human services programs,

mostly federal block grants and other public health and mental health spending.

Two major provisions shape the continued availability of public health services for undocumented residents. One

PRWORA provision declared that “not qualified immigrants” would be denied “federal public benefits.” Here, “not

qualified” meant all of the non-citizen statuses not included in the “qualified immigrant” list (see Helpful

Immigration Terms box and Appendix). However, most federal block grant programs that are focused primarily

on health care are not classified as federal public benefits, and so are not subject to immigration-status-based

restrictions. For example, federal maternal and child health, family planning, mental health and substance abuse,

and community health center funding were not subject to the new requirement. Federally-funded programs

providing these services do not, and in fact may not, exclude the undocumented. State and local programs that

supplement these federal funds with local revenues may not add their own immigration-related exclusions.

12

Essential Services that May Not Exclude Undocumented. A second key PRWORA provision directs that public

programs, whether federal, state or local, must not restrict access based on immigration status if they provide

any of the following:

Emergency Medicaid; and immunizations, or diagnosis (including testing) and treatment of communicable

disease (outside of Medicaid);

Shelters, soup kitchens, crisis intervention, and other non-cash assistance that is needed to protect life

and safety and is not limited to those with low incomes; or

Short-term, non-cash emergency disaster relief.

Public programs (and service providers) performing these functions not only are not required to verify

citizenship or immigration status (with the exception of Emergency Medicaid), they actually may not exclude

people because of immigration status.

Official federal standards explicitly name “medical and public health services, and mental health, disability or

substance abuse services necessary to protect life or safety” as services that must be available to all in need.

Federal guidance has clarified that even where a block grant is classified as a “federal public benefit,” some of the

services provided by the grant may be exempted, and therefore not restricted based on immigration status. This

protection “trumps” any exclusion of undocumented persons from a “federal public benefit,” so that for example

Title XX funding for a domestic violence shelter may be used for all victims regardless of immigration status, even

though Title XX is a “federal public benefit.”

Federally Qualified Health Centers are a critical source of care for low- and moderate-income mixed-status

families, because they combine comprehensive primary care resources with sliding-scale fees, accept Medicaid

and CHIP, and do not exclude non-citizens. They receive only limited federal funding for care for the uninsured,

so Texas’ decisions to limit Medicaid coverage of adults—both for U.S. citizens and for lawfully present

immigrants—increase the demand for those limited funds for the uninsured, putting pressure on the centers’

fiscal viability and their capacity to serve the remaining uninsured.

ACA Excludes Undocumented Immigrants from Marketplace Purchasing and Subsidies. Under the ACA,

individual undocumented residents may not enroll in coverage through the new state and federal Marketplaces,

and they do not qualify for premium or cost-sharing subsidies (these exclusions do not affect family members of

an undocumented person who are U.S. citizens or lawfully present non-citizens). Because they are excluded from

Medicaid, CHIP and the Marketplace, undocumented residents are also exempted from tax penalties for the

uninsured.

Key Federal Rules Insuring Access to Communicable Disease and Emergency Care

Together, the two provisions mean:

• All federal, state, and local programs—regardless of the funding source—that provide emergency or

crisis care, diagnosis or treatment of communicable disease, or immunization are open to non-U.S.

citizens regardless of their immigration status; and

• Any health program using federal health care funds—except for Medicaid and CHIP—must serve both

lawfully present and undocumented residents.

13

Texas Policy and Practice: Health Care Access for Undocumented Residents

Because of Texas’ high number of residents without health insurance (4.6 million uninsured in 2015, 17.1 percent

of Texans of all ages), local governments play a big role in connecting some of the neediest uninsured with health

care. However, though they generally meet the minimum federal and state legal standards regarding inclusion of

immigrants, local health care safety net programs in Texas vary considerably in whom they serve and what

services they provide.

Access to Emergency and Communicable Disease Care is Assured. As described above, federal law and guidance

forbid state or local programs from denying certain types of care “necessary to protect life or safety” based on a

person’s immigration status. And, state and local programs that co-mingle state or local revenues with federal

health care block grant funding may not deny care to undocumented immigrants in those programs. However,

federal law does permit state and local programs to exclude the undocumented in some circumstances, including

when the services provided are not necessary to diagnose or treat communicable disease or to protect life and

safety, and when no federal funds are used for the program.

Local Texas County Indigent and Hospital District Programs Choose Whether to Provide Comprehensive Care.

Policies of Texas Hospital Districts and County Indigent Health Care Programs to limit care for the undocumented,

and local practices regarding optional sponsor deeming and liability for qualified immigrants vary widely across

the state. A recent informal query of urban hospital district policies found that most of Texas’ largest urban

districts include undocumented residents in their programs for the uninsured, while most districts in the smaller-

population urban counties do not.

To comply with federal law, any counties that choose to exclude the undocumented from

their programs for the uninsured must nevertheless provide access to emergency care,

immunizations, diagnosis and treatment of communicable disease, and any other health

care interventions needed to protect life and safety, to all residents regardless of

immigration status. This requirement applies regardless of whether federal funds are used

by the county program.

Texas CHIP Perinatal Program: Prenatal, Delivery, and Postpartum Care. Federal law excludes all undocumented

residents from Medicaid, except via the Emergency Medicaid provisions. And, as explained above, Texas Medicaid

also excludes lawfully present pregnant women from full Medicaid maternity benefits. Federal and state funding

for prenatal care for women (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Block Grant, Title V) who are ineligible for Medicaid

historically was not adequate to meet Texas’ statewide need.

When a new CHIP option was created by federal regulation to provide prenatal care to the mother, on behalf of

the unborn future CHIP- or Medicaid-eligible U. S. citizen child, Texas adopted it. Approved by the state

Legislature in 2005 and launched in 2007, this program provides prenatal care benefits to both undocumented

and lawfully present immigrant mothers excluded from Texas Medicaid (as well as uninsured U.S. citizen women

between 185 and 200 percent of the FPL whose incomes are just above the upper limits for Medicaid maternity

benefits). Texas’ CHIP Perinatal program provides prenatal visits and limited postpartum care, with Emergency

Medicaid paying the bill for labor and delivery when the mother is a non-US citizen.

Birth Certificates for U.S. Citizen Children with Undocumented Parents. Birth certificates are issued in Texas by

local registrars, under authority and supervision of the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). Several

years ago, changes in state rules and policies resulted in the rejection by local registrars of many of the identity

documents accessible to the undocumented parents. Acceptable identification materials are required for the

14

parents to get a copy of their U.S. citizen child’s birth certificate. Advocates filed a federal lawsuit, arguing that the

restricted list of acceptable IDs made access to birth certificates impossible for many parents, and thus created

barriers to accessing school and church services for children, and made travel for the children impossible. In July

2016, the parties reached a settlement: the state of Texas agreed that its registrars would accept a number of

types of Mexican identification, including the electoral card, with similar guidelines to be adopted for Central

American countries. The parent must provide two such identification cards, or one such identification card

together with a two supporting documents. While official guidance on the settlement is not yet published, a

much-expanded list of “support docs” will be accepted (to supplement the identification document from the

country of origin), such as insurance cards, bank statements, loan documents, bills, rent receipts, medical records,

church records, and school records.

Readers are encouraged to report any continued problems with birth certificate access, so the court can ensure

that the new policies are being followed.

The Health Insurance Marketplace:

Coverage and Challenges for Immigrant and Mixed-Status Families

Since the Health Insurance Marketplace opened in October of 2013, Texas families that are made up of non-US

citizens, or of individuals with differing citizenship and immigration statuses—“mixed immigration status

families”— have faced all the same barriers to enrollment experienced by native-born uninsured. These included

federal Marketplace web and information technology systems that did not function in October and November

2013, lack of awareness of the available subsidies, confusion over timelines, and more. But immigrant and

“mixed-status” families faced additional potential barriers as well. In a recent nationwide survey of individuals

who assist consumers in the enrollment process, the majority of respondents said that enrollment of immigrants

took twice as long as enrollment of US-born citizens.

ii

Some of the areas of greatest concern and unmet needs

include:

System and Technical Barriers for Immigrant and Mixed-Status Families: Improved But Hurdles Still Exist

During its first few months of operation, the federally facilitated health insurance Marketplace (operated under

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)) used in Texas was initially unable to accurately record

information on immigration documents or to fully process an application for coverage and subsidies for those

households. For some applicants, this resulted in long delays in eligibility decisions, months without coverage, and

no ability for applicants or their advocates to find out about the status of their application, or to get help finalizing

a decision. Since these initial system failures, HHS has made large improvements to the website, and enrollment

into Marketplace coverage has improved. However, many barriers still remain for immigrants and mixed-status

families including:

greater difficulty verifying identity and proving income (e.g., for families headed by recent or

undocumented immigrants),

difficulty entering information related to their immigration status or citizenship documents for those born

outside the U.S., and

applicants with income under the poverty line being incorrectly assessed as potentially eligible for

Medicaid or falling into the Coverage Gap, instead of being determined eligible for subsidies.

15

Verifying Identity and Immigration Status

In a mixed-status family seeking benefits for the U.S. citizen and lawfully present members, but that includes one

or more undocumented earners, verifying whether family members meet income guidelines for Marketplace

benefits can be more challenging. Because the IRS does not rely on historical tax records that are tied to Individual

Taxpayer Identification Numbers (used by some workers without Social Security Numbers to file and pay federal

income taxes) to verify income, some families are required to provide additional income documentation to

complete their applications. In addition, the federal Marketplace’s identity-verification process relies on the use of

credit histories. This is problematic for recent immigrants, young people, and unbanked or underbanked persons,

as they are less likely to have a credit history and therefore must use the longer, manual process to verify their

identity.

For applicants who are lawfully present or who are naturalized citizens, verifying their citizenship or immigration

status can also be difficult, and may take weeks or months to complete. During the first open enrollment, the

Healthcare.gov website systems for real-time immigration verification functioned poorly, requiring families to

mail paper documents to the Marketplace instead. During the second and third open enrollment periods the

website functionality was greatly improved, glitches became less frequent, and HHS created a process for paper

documentation to be uploaded. However, the process for verifying immigration status in real-time still often does

not work even if all information is filled in correctly, and applicants are often required to submit additional

documents to finalize enrollment.

When immigration/citizenship status or income cannot be verified in real-time, most applicants are allowed to

enroll in coverage, but must provide the required documentation within 90 days. This is often called an

“inconsistency period.” If an applicant has an inconsistency related to immigration or citizenship status and she

does not provide the required documentation within the time frame her coverage will be cancelled. For income

inconsistencies, if the required proof of income is not provided the applicant’s subsidies may be cancelled or

reduced, but they will remain enrolled in coverage. Most people in this situation eventually cancel their coverage,

because without subsidies the coverage is unaffordable.

Marketplace Coverage Terminations

After the first open enrollment period due to the many system errors, the federal Marketplace provided

additional time for applicants to finalize the verification of their information. In May 2014, federal Marketplace

officials tried to contact close to a million people nationwide with discrepancies in their immigration and

citizenship records. The great majority submitted (or re-submitted) documents as requested, but about 115,000

of the original number (almost 20,000 in Texas) did not respond by September 2014 to a second outreach

attempt, and lost their coverage the next month. About 4,500 of these consumers had their coverage reinstated

retroactively after they provided the Marketplace with the documents requested.

After the second open enrollment, the Marketplace implemented the tighter time frame policy of providing just

90 days for applicants to clear data inconsistencies for income, immigration status, or citizenship before denying

coverage or adjusting subsidies. In total during 2015, coverage was terminated for about 500,000 consumers

nationwide with citizenship or immigration data matching issues and subsidies. In 2016 the numbers terminated

dropped substantially, to about 17,000 consumers with unresolved citizenship or immigration status data

matching issues. Compared to the first quarter of last year, this represents an 85 percent decrease in the number

of consumers whose coverage ended because of an unresolved citizenship or immigration data matching issue.

If consumers have the appropriate documents but their enrollment through the Marketplace was terminated

based on a citizenship/immigration status data matching issue, they are able to submit their documentation and

16

regain enrollment through the Marketplace outside of the usual open enrollment dates, through a Special

Enrollment Period (read more below).

Communications Barriers

Advocates and enrollment assisters continue to report that the process for providing required documentation

needs improvement. Many consumers reported submitting the same documents multiple times to no effect and

that notices do not clearly explain what information is needed. Furthermore, notices and call center assistance are

only available in English and Spanish and the Marketplace call center translation services for languages other than

Spanish can be cumbersome.

Misdirection

The design of the Marketplace application has caused many adult immigrants who are not eligible for Medicaid in

Texas to be routed unnecessarily to the state Medicaid agency. This additional unnecessary step can significantly

delay Marketplace enrollment. If an immigrant applicant with income below the poverty line indicates on the

application that they are “lawfully present” but the Marketplace is not able to electronically verify that person’s

immigration status (a frequent event), the system may then incorrectly assume that the applicant is either

Medicaid eligible (if they have kids and very low income) or that they are in the Coverage Gap. It will not recognize

that their immigration status makes them ineligible for Texas Medicaid. (Remember, most lawfully present

immigrants in Texas are eligible for Marketplace subsidies even if their income is below the poverty line, because

federal law specifically allows subsidies for legal immigrants below the poverty line, if they are excluded from

Medicaid on the basis of their immigration status.)

The system then assumes their application should be sent to the Texas Health and Human Service Commission for

a Medicaid determination. In a recent nationwide survey, enrollment assisters identified these unnecessary

transfers to state Medicaid agencies of individuals who are not eligible for Medicaid as their top priority for

improvements to the Marketplace application and enrollment process.

iii

“Special Enrollment Periods” and Exceptions to Tax Penalty

As discussed, getting the Marketplace to approve premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions for lawfully

present immigrants with incomes below the poverty line can be difficult and may take weeks or months. To help

address this issue, HHS made households facing these barriers eligible for a “special enrollment period” (SEP) that

allows them to continue to work with the federal Marketplace until they can get their applications correctly

processed, outside of the annual Open Enrollment period.

In addition to SEPs that help immigrants enroll in coverage, several exceptions to the tax penalty for being

uninsured also protect mixed-status families. Exemptions include special treatment of domestic violence

survivors, families with income low enough that they aren’t required to file taxes, and families who encountered

any one of a wide variety of hardships through the year. Neither the SEPs nor the tax penalty exemptions provide

retroactive coverage for Marketplace insurance, so families who face delays in coverage may still have to deal

with medical debts they accumulated while waiting to get coverage.

Marketplace Affordability in Question for Some Non-Citizens

Lawfully present immigrants in below-poverty income households can (unlike their U.S. citizen neighbors) buy

coverage in the Marketplace. When they do, many can get subsidies that were intended and designed for

households at or above the poverty line. They may pay as much as 2 percent of their income for monthly

premiums, plus additional out-of-pocket amounts when they get services and medications. It is too soon to assess

to what extent these costs may prove prohibitive for families below the poverty line.

17

Policy Barriers that Can Affect any Low-Income Uninsured, Including Immigrants

Several ACA flaws affect both U.S. citizens and lawfully present people. A portion of mixed-status families at

various incomes will also experience the so-called “family glitch.” Federal rules deny subsidies to spouses and

children where one working parent has “affordable” worker-only coverage, even though the out-of-pocket costs

to insure the spouse and children may be prohibitive. This illogical policy is an unintended result of the Internal

Revenue Service’s interpretation of the ACA’s language, and one which can only be fixed if Congress is able to

make corrections to the ACA. The likelihood of Congress achieving technical corrective changes to the ACA has so

far been diminished by the broader political battle over the law, with opponents seeking to repeal the law rather

than improve it.

Another affordability barrier can occur when low-income parents are separated but not divorced, because

Marketplace subsidies are not available for households when a married couple files separate income tax returns.

The high cost of divorce, complex immigration concerns, and cultural attitudes toward divorce all can contribute

to families being cut off from Marketplace subsidies—and affordable comprehensive care—in these situations.

Families with highly unpredictable earnings that may change from week to week or month to month may also

find it more difficult to calculate the right premium subsidies, or to verify their current or predict their future

income. Incomes of workers who are paid routinely with cash or without a formal payroll check may not be

verifiable through online wage databases. Households can get assistance with these challenges, but the need to

resort to manual income documentation can result in delays in coverage for the families with the least resources.

Systems for Resolving Complex Cases Lacking

Finally, the Health Insurance Marketplace website and systems were designed to streamline eligibility and

enrollment for most applicants. However, these systems often do not meet the needs of families with more

complex or non-traditional circumstances such as mixed immigration statuses, non-traditional family structure,

and unpredictable earnings. Currently, the federal Marketplace does not provide a robust support system through

which complex cases can be referred to expert staff and addressed quickly. More should be done to increase the

numbers of trained Marketplace staff that can perform complex casework, and thereby reduce the need to use

the formal appeals process.

Understanding How Families Can Get Caught in the “Family Glitch”

No-Glitch Example:

The Garcia family needs health care for the two parents, Don and Ann, ages 35 and 33, living in Travis County,

TX. Don and Ann are both lawfully present immigrants, and their two school-age daughters are U.S. citizens.

With a family of four and income of $35,600, their income is about 150 percent of the FPL. Their two children

are enrolled in CHIP (with no monthly fee), but neither Don nor Ann’s job offers health benefits.

In the marketplace, Don and Ann qualify for a $352 per month tax credit, allowing them to pay $121 each

month for a health plan that would have cost $473 per month without a subsidy.

Family Glitch Example:

Don’s employer offers a health plan, and pays half of his premium. The employer “offers” coverage for Ann

and the children, but does not pay any of the premium. Under law, because Don’s one-half share of his

worker-only premium is less than 9.5 percent of his family income, Ann and the girls cannot get premium

subsidies in the Marketplace. Fortunately, the girls can get CHIP, but Don and Ann face spending $355 a

month for coverage (half of his job-based premium, plus 100 percent of the cost of her Marketplace plan).

This is 12 percent of their monthly income.

18

Recap: Many Gaps Persist in Access to Care for Immigrants in Texas

With over 4.6 million uninsured Texans in 2015, substantial gaps in access to health care will remain a problem for

many Texans in the near term, despite the important gains and new options provided by the ACA. Listed below is

a partial inventory of notable holes in the Texas health care safety net for non-U.S. citizen residents.

Undocumented

The greatest access gaps for non-citizens affect Texans without legal immigration status. Barred from Medicaid,

CHIP, and the Marketplace and its subsidies, private health coverage is available only to undocumented

individuals who have adequate income to purchase a policy at full price, without a subsidy. Undocumented

residents can look to Federally Qualified Health Centers, some (but not all) urban hospital/health districts, and

independent charity clinics for care, meaning that access to affordable care is highly variable depending on

where an immigrant lives in Texas.

Lawfully present

Immigrants who are lawfully present in the U.S. face certain barriers that are specific to their non-citizen status, as

well as some of the same barriers affecting U.S. citizens.

The Coverage Gap traps some lawfully present, including refugees and asylum seekers. Most lawfully

present individuals with incomes below 100 percent of the FPL can qualify for subsidies in the ACA

Marketplace. However, certain lawfully present immigrants are caught in the Coverage Gap in states like

Texas that have not accepted federal ACA funds to extend Medicaid to adults who earn less than 138

percent of the FPL. So the categories of legal immigrants that Congress intended in 1996 to have access

to Medicaid and CHIP, actually are the very ones who are left without coverage options in Texas and

other states that have not expanded Medicaid.

Texas law excludes most lawfully present immigrant adults from Medicaid. The state legislature would

have to authorize a change to this state policy (adopted in 1999) in order for a Texas solution to insure

low-income Texans in the Coverage Gap to also benefit lawfully present adults below the poverty line.

Technical Marketplace application processing issues for individuals with immigration documents, as well

as for mixed-status families have delayed coverage and discouraged eligible Texans from completing

enrollment. Improved Marketplace performance during the second and third open enrollment period

appears to be improving enrollment rates but further improvement is still needed.

The “family glitch” affects both lawfully present immigrants and U.S. citizens. These families may not

qualify for premium subsidies in the Marketplace , and face either paying full price and an unlimited,

unaffordable percentage of their incomes for job-based or Marketplace insurance premiums, or

remaining uninsured.

Affordability issues occur even for families that have access to premium subsidies and out-of-pocket help

in the Marketplace. Those below poverty may have a hard time affording 2 percent of income in

premiums with additional copayments and deductibles. Families at any income level who experience high

health care needs may face spending up to 20 percent of income before deductibles and out-of-pocket

caps kick in.

Separated, but not divorced, parents may not have access to Marketplace subsidies because of tax filing

status or lack of access to income information on the absent spouse.

19

Hard-to-verify incomes. The income verification systems that the Marketplace and state Medicaid-CHIP

programs rely on can work well for those with steady employment and predictable hours and wages. They

are less helpful for those working irregular hours, multiple jobs, or being paid cash or by hand-written

check. Advocates will need to monitor the systems to identify and try to reduce any barriers to

enrollment, renewal, or qualifying for premium subsidies that may result from the additional

documentation families in these situations may have to produce on an ongoing basis.

As we publish this report in late 2016, few solutions to the barriers listed above are truly in the pipeline. In the

Marketplace open enrollment periods for 2015 and 2016 coverage, systems to accept immigration documents

from lawfully present family members were working substantially better than in the first period. Still, large

numbers of families face multiple barriers in the Marketplace. Application assisters report families who struggled

to complete applications in a previous year lack confidence that their information will be processed promptly and

accurately in the next year.

Apart from gradual technological improvements, the remaining barriers will require concerted attention and

advocacy at the state and federal levels, as well as local solutions to maintain or expand safety nets for the

undocumented residents who are excluded from state and federal programs.

Protecting Access in Your Texas Community:

How You Can Help, and How to Get Help

As noted at the opening of this report, a number of policy challenges to immigrants’ access to care have

arisen in Texas over the last two years. Legislation to reduce access to care for undocumented children in

Texas’ Children with Special Health Care Needs Program was filed and only narrowly defeated in 2015. The

Department of State Health Services was served with a lawsuit, after some local officials stopped issuing

birth certificates to undocumented parents of U.S. citizen children (positive settlement reached July 2016).

Tom Green County requested a state Attorney General’s opinion on whether counties should discontinue

services to undocumented residents in the County Indigent Health Care Program. In related matters,

interim legislative studies were charged with examining state and local laws applicable to undocumented

immigrants, and questioning Texas’ official involvement in the Refugee Resettlement Program. In

September 2016, Texas Governor Greg Abbott announced that Texas will withdraw from the federal

refugee resettlement program.

iv

A new presidential administration will take office in January 2017, which based on its campaign rhetoric

may be expected to promote harsher public policy toward non-U.S. citizens, and could weaken the

existing federal protections of the rights of immigrants.

In light of these recent pressures, CPPP hopes this report will help community organizations, health care

providers, and other stakeholders interested in supporting access to health care for all members of the

community. The Center can also offer support in two other ways:

Group training on the policies in this report, in your community or via webinar; and

Trouble-shooting assistance when you have questions about whether laws and rules are being

followed regarding immigrants’ access to coverage or care.

To inquire about training or other assistance for your organization, please contact CPPP at

dunkelberg@cppp.org.

20

Next Steps for Texas: Policies to Improve Health Care Access and Outcomes

Federal law, Texas law and the state constitution combine to make Texas cities, counties, and hospitals the

providers and funders of last resort for all of the uninsured. U.S. and Texas law allow federal and state

government to reject the health costs of uninsured immigrants—lawfully present and undocumented alike—and

shift them to local governments and health care providers. In this way, Texas’ policy decisions to turn down

available federal support for the uninsured take a toll on local taxpayers, and on all the other services

communities need to fund.

CPPP recommends that Texas make the following three key policy changes to increase federal funding for

coverage and care of immigrants:

1. Providing Medicaid Maternity benefits to lawfully present immigrant women. Texas should provide

comprehensive pregnancy benefits on par with those of U.S. citizens. Today, even legal permanent residents

are treated the same as undocumented mothers.

2. Closing the Texas Coverage Gap, and insuring all citizens 19-64 up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line

($27,724 for a family of 3). This step would do even more than #1 for maternal health, by allowing women

access to medical homes before conception for healthier pregnancies, continuing their care after birth to

screen for and treat chronic medical conditions, and thereby improving health for any future pregnancies.

This improved care will be gained equally if accomplished via an 1115 “red state waiver” conservative

alternative.

Closing the Gap will also eliminate today’s perverse policy which denies access to coverage to immigrants

Congress intended to protect: e.g., active-duty military and veterans, victims of human trafficking, and

refugees. Step #2 will also dramatically improve payments to hospitals and doctors for emergency care to

uninsured undocumented residents.

3. Providing Medicaid benefits to lawfully present immigrants aged 19 and older. Lawmakers should also

reverse the Texas law that now excludes these adults, in order to maximize the reduction in uninsured

lawfully present Texans and the relief for local governments that closing the Coverage Gap would bring. Texas

Medicaid today covers very few U.S. citizen parents and adults under current policy: e.g., 3 million children

are enrolled, but only 150,000 of their parents. Unless Texas begins providing coverage options for U.S. citizen

parents and other adults living in poverty, reversing Texas’ ban on Medicaid for lawfully present immigrant

adults will have limited effect.

Of course, the steps described above do not fully address the barriers to care for undocumented residents and the

costs of their care born by local governments and care providers. Texas should take the lead among the states,

squarely face the realities and negative consequences of these barriers for our communities, and develop a

proactive strategy to improve systems and financing of care for the undocumented uninsured.

21

Helpful Resources

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Health Reform Beyond the Basics; slide decks provide detailed

information on application and eligibility issues and processes;

http://www.healthreformbeyondthebasics.org/category/issues/immigrant-eligibility-for-premium-tax-credits-

and-medicaid/

A Comprehensive Review of Immigrant Access to Health And Human Services

http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/11/immigrantaccess/review/index.pdf

Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs – see page 4 for a list of “qualified” immigrants.

http://www.nilc.org/document.html?id=108

Getting Enrollment Right for Immigrant Families; http://ccf.georgetown.edu/ccf-resources/getting-enrollment-

right-immigrant-families/

Immigrants and the ACA - http://nilc.org/immigrantshcr.html; http://nilc.org/immigrantshcrsp.html ;

https://www.healthcare.gov/what-do-immigrant-families-need-to-know/

Sponsored Immigrants & Benefits - http://www.nilc.org/document.html?id=166

“Lawfully Present” Individuals Eligible under the Affordable Care Act -

http://www.nilc.org/document.html?id=809

Frequently Asked Questions – Exclusion of Youth Granted “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals” from

Affordable Health Care - http://www.nilc.org/document.html?id=802

Verification & documentation - http://nilc.org/document.html?id=35 ;

https://www.healthcare.gov/help/immigration-document-types/ ; https://www.healthcare.gov/help/citizenship-

and-immigration-status-questions/

Federal Guidance on Public Charge – When Is it Safe to Use Public Benefits? -

http://www.nilc.org/document.html?id=164

Confidentiality and reporting fears - http://www.ice.gov/doclib/ero-outreach/pdf/ice-aca-memo.pdf

Linguistic and cultural barriers - https://www.cuidadodesalud.gov/es/ ;

http://marketplace.cms.gov/getofficialresources/other-languages/other-languages-materials.html ;

http://www.hhs.gov/open/execorders/13166/index.html

22

Appendix: Deeper Background on Federal Policy on Immigrants’ Access to Health Care

Federal immigration and welfare laws passed in 1996 and after have made big changes to non-US citizens’ access

to health care and safety net services, for both lawfully present immigrants and for those lacking legal status. The