CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | AUGUST 2024

Report on Contract for

Deed Lending

Table of contents

Table of contents......................................................................................................... 1

1. Executive summary .............................................................................................. 2

2. Consumer harms associated with contracts for deed ...................................... 5

3. The history of predatory contracts for deed .................................................... 12

4. Investors fueled a resurgence in contracts for deed ....................................... 14

4.1 Atlanta .................................................................................................... 16

4.2 Minneapolis ............................................................................................. 17

4.3 Detroit ..................................................................................................... 18

4.4 Texas Border Colonias ............................................................................ 19

5. Contract for deed sellers may exploit—and perpetuate—market

distortions ........................................................................................................... 22

6. Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 25

Appendix A: The history of predatory contracts for deed ................................. 26

1 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

1. Executive summary

Contracts for deed are a form of seller financing, where the seller retains legal title of a home

until the borrower completes the payments.

1

1

See Restatement (Third) Property (Mortgages) § 3.4(a) (Am. L. Inst. 1997) (“A contract for deed is a contract for the

purchase and sale of real estate under which the purchaser acquires the immediate right to possession of the real

estate and the vendor defers delivery of a deed until a later time to secure all or part of the purchase price”). On

August 13, 2024, the CFPB released its Advisory Opinion on the Truth in Lending Act as it relates to Contracts for

Deed. See CFPB Advisory Opinion: Truth in Lending (Regulation Z); Consumer Protections for Home Sales

Financed Under Contracts for Deed.

Contracts for deed are also known by other names,

sometimes including “land contracts,” “installment land contracts,” “land sales contracts,” or

“bonds for deed.”

2

2

Restatement (Third) Property (Mortgages) § 3.4 cmt. a (Am. L. Inst. 1997); Amy Fontinelle & Rachel Witkowski,

Land Contract: What It Is & How It Works, Forbes Advisor (Sep. 27, 2021),

https://www.forbes.com/advisor/mortgages/what-is-a-land-contract/. Despite the various names, and differences

in the specific operation of these agreements, their core characteristics are the same. In this paper we use “contracts

for deed” to refer to all such agreements.

During the contract term, the borrower typically assumes the responsibilities

of homeownership, including repairs, property taxes, and improvements. The contracts usually

provide for forfeiture in event of any default in the contract terms, such as missed payments.

Upon forfeiture, the seller may repossess the home and retain all accumulated equity and

payments, including the buyer’s downpayment and improvements made to the property. Buyers’

exercise of their rights regarding the property is often complicated because the contract showing

the buyer’s interest is not recorded. Key findings of this report follow:

Substandard housing, title defects, and inflated prices can create problems

for homebuyers. While some contracts for deed can provide sustainable paths to

homeownership, seller-financers often do not assess the borrower’s ability to repay the

loan. Many contracts for deed include inflated home prices and higher interest rates than

mainstream mortgages. Some also have large balloon payments at the end of the term.

Substandard housing conditions can require expensive repairs and improvements paid

for by the borrower and can severely impact the quality of life for borrowers and the

surrounding community. Title defects can limit the borrower’s ability to assume legal

title to the home or to later sell it and can result in the borrower losing all equity in the

home. Because forfeiture provisions allow lenders to reclaim the home and retain the

borrower’s payments and the value of any repairs, sellers or investors can profit from

borrowers’ inability to sustain homeownership under contracts for deed.

3 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Contrac

t for deed loans were long marketed to Black borrowers. From the

1930s well into the 1960s, when Black borrowers were largely barred from obtaining

more affordable loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), sellers

marketed contracts for deed to Black borrowers to purchase homes at inflated prices.

Contract for deed loans continue to be marketed to traditionally underserved and

underinvested communities.

Driven by investors, contract for deed loans surged during the Great

Recession. Over 7.5 million homes were lost to foreclosure between 2007 and 2016.

3

3

CoreLogic, United States Residential Foreclosure Crisis: Ten Years Later, 3 (March 2017),

https://www.corelogic.com/wp-content/uplo

ads/sites/4/2021/07/National-Foreclosure-Report-Ten-Years-

Later.pdf.

Invest

ors purchased foreclosed homes in bulk at low prices. Investors then resold and

financed many of these homes through contracts for deed. Some investors sold the same

home back to the same family who had previously lost it through foreclosure, albeit at a

much higher price than either the owner or the investor had paid to acquire the home.

Today, contract for deed loans are disproportionally concentrated in low-

income, Black, Hispanic, immigrant, and some religious communities. These

include many of the same communities that were redlined and experienced

disproportional foreclosures during the Great Recession. Contract for deed providers

have also targeted Muslim borrowers with claims that their product complies with

certain religious practices forbidding the paying of interest.

Contracts for deed can harm housing markets by causing or perpetuating

substandard housing stock, inflated home prices, and less access to

mainstream mortgage credit. They create and perpetuate substandard housing

stock, as sellers can generate profit by repeatedly selling homes without maintaining

them, also known as churning. They can also perpetuate a lack of mainstream mortgage

lending in underserved and underinvested communities if the seller only makes the

properties available for sale using a contract for deed and will not accept a sale financed

with a bank loan. Additionally, the lack of appraisals and inspections permits sales prices

at inflated values.

Several federal laws under the CFPB’s jurisdiction provide consumer protections that may apply

to practices associated with contracts for deed, including the Consumer Financial Protection

Act’s prohibition against unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts and practices, the Fair Credit

4 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Repo

rting Act, the Truth in Lending Act, the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act, and the

Equal Credit Opportunity Act. Many of these laws also have private rights of action, which allow

individuals to sue on their own behalf. State attorneys general also have authority to enforce

these laws, as well as state and local laws that may provide additional protections to borrowers.

The federal Fair Housing Act provides additional protections, including a private right of action.

5 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2. Consumer harms associated

with contracts for deed

Contracts for deed are loans where the seller retains legal title of a home until the borrower

completes the course of payments. Their payback period may vary from a few years to twenty

years or more. While some contracts for deed can provide sustainable paths to homeownership,

4

4

See The Pew Charitable Trusts, Land Contracts Pose 5 Major Risks for Homebuyers, July 18, 2024,

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2024/07/land-contracts-pose-5-major-risks-

for-homebuyers (“87% of respondents to Pew’s survey who had either left or repaid a land contract rated their

experience as somewhat or extremely positive, 88% said that they eventually achieved homeownership, and about

56% reported that they still own their land contract-financed property”).

they often pose substantial risks. During the contract term, the borrower assumes the financial

responsibilities of homeownership, including property taxes, hazard insurance, repairs, and

improvements. However, contracts for deed can lack many of the consumer protections available

with mainstream mortgages and may be structured in a manner that exposes borrowers to harm

over the entire life cycle of the agreement.

5

5

Heather K. Way & Lucy Wood, Contracts for Deed: Chartering Risks and New Paths for Advocacy, 23 J. Affordable

Housing & Cmty. Dev. L. 37, 40 (2014) (contract for deed “transactions lack many of the safeguards available to

buyers in traditional third-party mortgages —with weaker legal protections and no bank, government agency, or

title closing agent overseeing the transaction. As a result, homebuyers utilizing seller financing are prime targets for

a host of abusive practices by unscrupulous sellers.”).

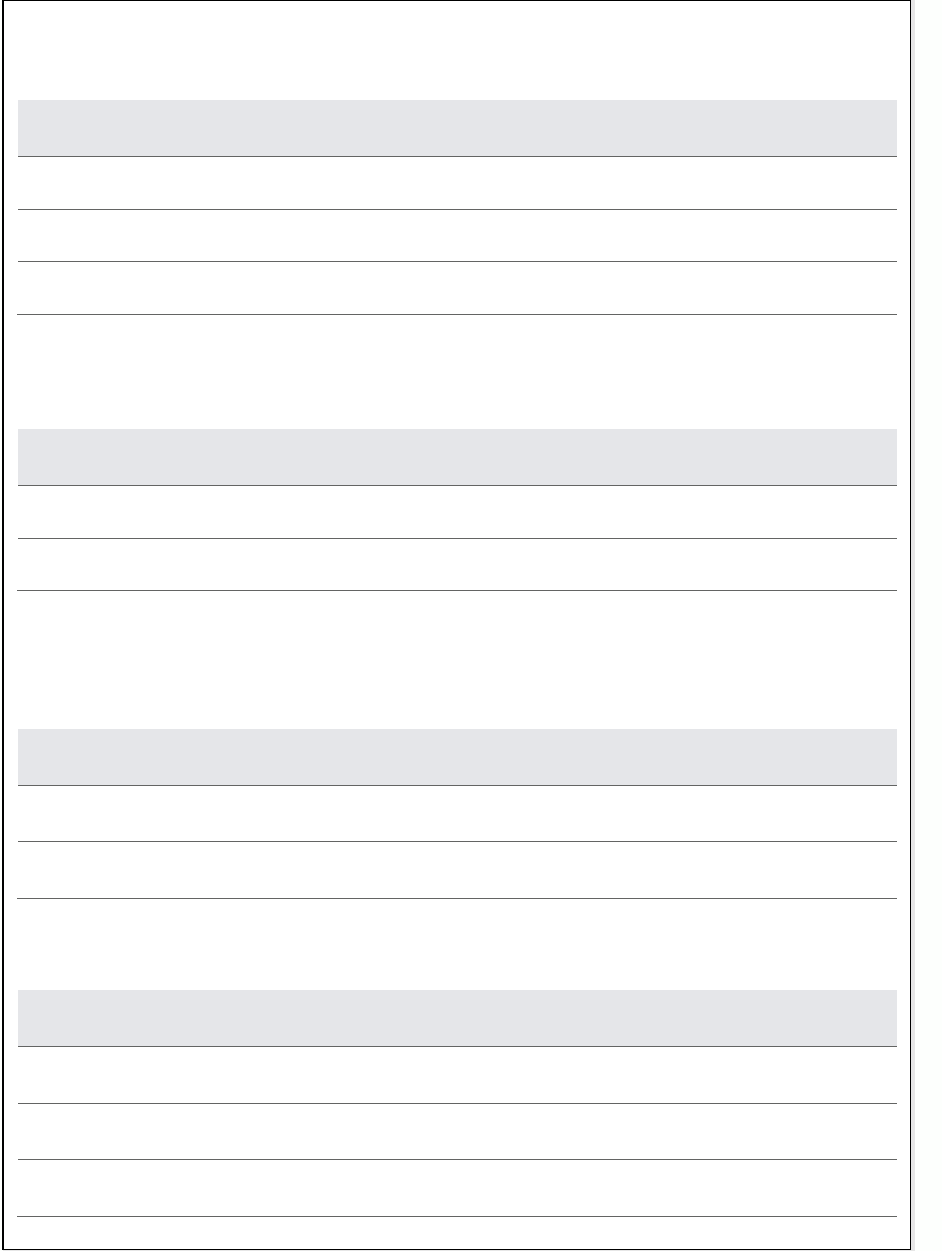

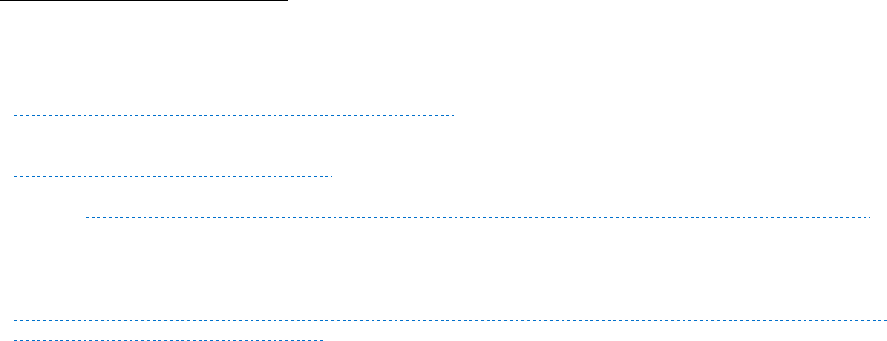

Tables 1A-D below highlight some common mainstream mortgage protections for borrowers and

identify those features that are often not present in contracts for deed based on common market

practices. The tables are designed to broadly highlight some of the potential harms consumers

may face when entering into a contract for deed, without addressing all the variations in market

practices and state and local legal requirements. Some of the market practices in these tables are

6 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

not co

mpliant with existing legal requirements under state or federal law.

6

6

For example, the Truth in Lending Act requires covered creditors to disclose the finance charge on any loan.

Contracts for deed generally have a finance charge, often including interest, but the finance charge may not be

disclosed to borrowers. In some cases, creditors will assert there is no interest for the product, but will make other

adjustments to the contract terms, including raising the sales price, in an amount equal to imputed interest. In that

case, the finance charge is actively concealed from the borrower, in violation of the Truth in Lending Act. Contracts

for deed sold by TILA creditors are covered by federal TILA disclosure requirements. See CFPB Advisory Opinion,

supra note 1.

Some contracts for

deed are compliant with the law, and not all contracts for deed have all of these features.

7

7

For example, after default, mainstream mortgages must follow certain state and local law procedures (arbitration,

mediation, required filings and notice, recordings, etc.) before a creditor can complete foreclosure. These

procedures, and the extent to which contracts for deed are included in those protections, vary extensively by state.

7 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

TABLE 1A: PROPERTY UNDERWRITING PROCESSES

Property underwriting process features protect both borrowers and creditors. They ensure that

properties are worth the purchase price and that they are legally free to be sold to the borrower.

Typical Features in Loan Products to

Purchase Homes

Mainstream

Mortgages

Contracts for

Deed

Appraisals performed Yes No

Home inspection performed Yes No

Title Search Performed Yes No

TABLE 1B: L

OAN DISCLOSURES

Certain features allow borrowers the ability to shop around and compare multiple loan offers to

ensure they receive the best interest rate and fees for their loan.

Typical Features in Loan Products to

Purchase Homes

Mainstream

Mortgages

Contracts for

Deed

Interest rate disclosed Yes Varies

Disclosures provided Yes No

TABLE 1C:

OWNERSHIP FEATURES

Ownership features ensure borrowers retain title to the home during the loan term. They also

enable borrowers to pursue sale of the home, take out home equity loans to make repairs, and

refinance the home loan during the loan term if needed.

Typical Features in Loan Products to

Purchase Homes

Mainstream

Mortgages

Contracts for

Deed

Legal title transferred upon entering into

contractual agreement

Yes No

Borrower may sell home, obtain secondary

liens, or refinance during the loan term

Yes No

TABLE 1D: DEFAULT PROCESS FEATURES

Loss of property occurs only after legal foreclosure procedures.

Typical Features in Loan Products to

Purchase Homes

Mainstream

Mortgages

Contracts for

Deed

Pre-foreclosure review periods (e.g., Federal

120-day pre-foreclosure review period)

Yes No

Foreclosure procedures occur before

property may be seized

Yes No

Borrower entitled to receive any surplus from

foreclosure sale of home

Yes No

8 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Avoiding

Obligations to Provide Habitable Properties: A contract for deed transaction may

provide a seller with an opportunity to avoid repair obligations that ordinarily extend to a

landlord.

8

8

See Eric T. Freyfogle, The Installment Land Contract as Lease: Habitability Protections and the Low-Income

Purchaser, 62 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 293, 296 (1987) (“As sellers rather than landlords, they can shift repair duties to the

home residents and can profit from substandard housing—all in contravention of the public policies underlying the

warranty of habitability”).

A seller can place a contract for deed borrower in a substandard home, without the

benefit of the inspection associated with mainstream mortgage financing that identifies defects

in the home and usually results in the home being brought up to code.

9

9

See, e.g., Installment Sales Cont. Act, 765 Ill. Comp. Stat. 67/10(c)(20), (26) (sellers may make borrowers financially

responsible for certain repairs, even for homes with known defects, including condemned dwellings, as long as the

defects are disclosed).

Borrowers sometimes

enter into contracts for deed only to find out after the fact that expensive repairs are necessary

to make the home habitable.

10

10

M

atthew Goldstein & Alexandra Stevenson, Market for Fixer-Uppers Traps Low-Income Buyers, N.Y. Times (Feb.

20, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/21/business/dealbook/market-for-fixer-uppers-traps-low-income-

buyers.html; Jeffrey Meitrodt, Contract for Deed can be House of Horror for Buyers, Star Tribune (July 5, 2013),

https://www.startribune.com/jan-14-contract-for-deed-can-be-house-of-horror-for-buyers/185756982/; Fair

Housing Center of Central Indiana (FHCCI), The State of Fair Housing in Indiana Report - Land Contracts: The

Promise and Perils of Alternative Home Financing 9 (June 30, 2024) (a contract for deed borrower may

unknowingly have to spend money at the beginning of the contract to bring their home into a livable condition,

which could limit their ability to make monthly payments and put them at risk of default).

Lack of Competition in Home Pricing: Some contract for deed sellers target low-income

borrowers with offers of affordable homes.

11

11

Jeremiah Battle, Jr., Sarah Mancini, Margot Saunders, & Odette Williamson, Toxic Transactions: How Land

Installment Contracts Once Again Threaten Communities of Color, Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr. 4-5 (July 2016),

https://www.nclc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/report-land-contracts.pdf.

Yet, the contract prices can exceed the true value of

the home and may not reflect the costs of needed repairs or unpaid back taxes or other existing

liens on the properties.

12

12

Meitrodt, supra note 10.

Borrowers may agree to the contract prices without knowing the true

value of the homes, given that appraisals are not required for the transactions.

13

13

Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 8.

Where sellers

control a significant portion of the housing stock within an area, or represent themselves as the

sole provider of financing, they are able to inflate home prices more easily.

Lack of Competition in Loan Pricing: Contract for deed sellers may present themselves as the

sole financing option for the homes and thus may not have to compete on loan pricing, which

could limit consumer choice.

14

14

See, e.g., David Migoya, Denied loan at bank, buyers have few options: Many applicants not ‘credit-worthy,’

Belleville News-Democrat (Illinois) (May 18, 1993), at 1A.

Accordingly, they may charge rates above the prevailing

9 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

mort

gage rate.

15

15

Goldstein & Stevenson, supra note 10 (finding contract for deed interest rates of 9.9 percent); Shelayne Clemmer,

Texas’s Attempt to Mitigate the Risks of Contracts for Deed—Too Much for Sellers—Too Little for Buyers, 38 Saint

Mary’s L.J. 755, 799 (2007) (finding contract for deed interest rates in Texas between 12 and 14 percent).

In addition, some contracts for deed are not fully amortized and require the

borrower to pay a substantial balloon payment at the end of the payment schedule or risk losing

the property and all accumulated equity.

16

16

See Fed. Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (Minneapolis Fed), Risks and Realities of the Contract for Deed, (Jan. 1,

2009), https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2009/risks-and-realities-of-the-contract-for-deed.

In one example from 1993 of a loan from East St.

Louis, Illinois, in 1993, that was not fully amortizing, the principal balance increased to

$106,320 on a $19,037 home.

17

17

Editorial, Breaking the Cycle, Belleville News-Democrat (Illinois) (May 19, 1993), at 4A.

Sellers H

ave Incentive to Repeatedly Sell the Same Home using a Contract for Deed: Many

contracts for deed permit sellers to evict borrowers for any default, including a single missed

payment or lapse of insurance.

18

18

See, e.g., Perdue v. Jamison, No. 28324, 2019 WL 5856669, at *1, *6-10, (Ohio Ct. App. Nov. 8, 2019) (finding that

a land contract borrower had forfeited her rights under a land contract per Ohio law when the borrower failed to pay

real estate taxes and obtain general liability insurance pursuant to the terms of the land contract that stated “[i]n

the event of default and termination of [the land contract] . . . , the [borrower] forfeits any and all payments made

under the terms of [the land contract], including but not limited to all payments made towards the [p]urchase

[p]rice, and any and all taxes, assessments, or insurance premiums paid by the [borrower]”).

Under the contract terms, sellers are generally entitled to retain

all payments made by the borrower and any improvements the borrower has made to the

home.

19

19

See, e.g., Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr., Summary of State Land Contract Statutes, 6 (Apr. 30, 2021) (“forfeiture allows

a seller to cancel the contract based on any default, even a trivial one, simply by notifying the consumer that it is

canceled, and then commence an eviction proceeding. The seller is permitted to keep the home, whatever its value,

and keep all the money the consumer has paid … In some states, including many that have enacted land contract

statutes, courts have allowed virtually unrestricted use of forfeiture clauses.”), https://www.pewtrusts.org/-

/media/assets/2022/02/summary-of-state-land-contract-statutes.pdf; N.C. Gen. Statute §§ 47H-3, 47H-4 (contract

for deed forfeiture provisions are executed after notifying the borrower and providing at least 30 days to cure);

Wash. Rev. Code §§ 61.30.010, 61.30.020, 61.30.030, 61.30.090 (contract forfeiture provisions are executed by the

seller after providing and recording required notices).

As a result, borrowers can lose all of their accumulated equity if they miss or are late on

a single payment. In contrast, lenders of most mainstream mortgages must wait 120 days after

the first missed payment before beginning the foreclosure process,

20

20

12 CFR § 1024.41(f)(1).

which can allow time for

the borrower to catch up, refinance the loan, sell the house, or obtain a loan modification or

other accommodation from the lender.

10 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

High F

ailure Rate: Some experts estimate that more than 50% of contracts for deed result in

loss of the home.

21

21

Exploiting the American Dream: How Abusive Land Contracts Prey on Vulnerable Homebuyers: Hearing Before the

Subcomm. on Hous., Transp. & Cmty. Dev., of the Sen. Banking Comm., 118th Cong. 9, n.30-31 (2023) (statement

of Sarah Bolling Mancini, Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr, citing a survey of legal services attorneys in Florida, Georgia,

Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia). See also

David Migoya, Home Buyers' Dreams Fade, Belleville News-Democrat (Illinois) (May 16, 1993), at 1A, 8A (63% of

one seller’s bond for deed accounts had balances higher than the selling price).

Researchers at the University of Texas-Austin found over a 21-year period

that 45% of contract for deed borrowers in the Texas border colonias

22

22

The term “Colonias” has been applied generally to unincorporated communities along the United States-Mexico

(US-Mexico) border in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas that often are associated with high poverty rates

and substandard living conditions. The Colonias are defined primarily in reference to a lack of potable drinking

water, water and wastewater systems, and paved streets. Housing Assistance Council, Colonias Investment Areas:

Working Toward a Better Understanding of Colonia Communities for Mortgage Access and Finance, 3 (Nov.

2020), https://www.fanniemae.com/media/37566/display

.

defaulted and fewer than

20% obtained a deed to their home.

23

23

See Peter M. Ward, Heather K. Way, & Lucille Wood, The Contract for Deed Prevalence Project: A Final Report to

the Texas Dep’t of Hous. and Cmty. Affairs (TDHCA), at ch. 3: 13 (Aug. 2012),

https://www.tdhca.state.tx.us/housing-center/docs/CFD-Prevalence-Project.pdf

.

The Pennsylvania Attorney General found that over a six-

year period, 79% of one seller’s contract for deed loans failed within a few years.

24

24

Complaint, Pennsylvania v. Vision Prop. Mgmt., LLC, No. GD-19-014368, at ¶ 76 (Ct. Common Pleas Allegheny

Cnty, Pa. Oct. 10, 2019) (within a six year period approximately 85% of Vision Property Management, LLC and its

affiliates contracts for deed were terminated with only approximately 6% of the terminations due to the borrower

owning the home in question).

In contrast,

during the Great Recession, the national foreclosure rate was 4.6%, including a rate of 15.6%

among subprime loans.

25

25

See U.S. Census Bureau 2012, Table 1193: Mortgage Originations and Delinquency and Foreclosure Rates: 1990 to

2009, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2010/compendia/statab/130ed/tables/11s1193.pdf.

Today, the overall foreclosure rate stands at approximately 0.3%.

26

26

See, e.g., CoreLogic: US Mortgage Delinquency, Foreclosures Rates Hover Near Historic Lows in February (Apr.

25, 2024) (calculating the share of mortgages in some stage of the foreclosure process as 0.3% in February 2024,

unchanged from February 2023),

https://www.corelogic.com/press-releases/corelogic-mortgage-delinquency-

foreclosures-hover-near-historic-lows-february/.

Lack of

Protections Upon Default: In general, some contracts for deed permit sellers to evict

borrowers, subject only to a minimal process under state law. And unlike mainstream

mortgages, contracts for deed may not provide a foreclosure process or other traditional

protections normally available to borrowers,

27

27

Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 3 (land installment contracts are popular with investors because they can quickly

evict defaulting borrowers without having to address mainstream mortgage foreclosure protections for defaulting

borrowers).

such as the right to a foreclosure sale and receipt

of any surplus funds generated by the sale.

28

28

Restatement (Third) Property (Mortgages) § 3.4, cmt. b(1) (Am. L. Inst. 1997) (many states provide mainstream

mortgage holders a right of redemption, which gives the defaulting borrower the ability to redeem his property);

Heather K. Way, Informal Homeownership in the United States and the Law, 29(1) St. Louis U. Pub. L. Rev. 113,

139–40 (2009).

In Detroit, researchers found that 31 % of

properties held within certain large portfolios of contracts for deed were subject to landlord

11 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

actio

ns—the means by which contract for deed occupants are evicted.

29

29

Joshua Akers & Eric Seymour, Instrumental Exploitation: Predatory Property Relations at City’s End, 91

Geoforum 127, 137 (2018).

The CFPB has received

reports that borrowers can be intimidated by seller notices of default and functionally self-evict

by abandoning their homes, leaving behind their downpayment and investments in

improvements to the home.

Undisclosed Title Defects Can Hinder Assumption of Legal Ownership: A title search may not

be performed for contract for deed transactions, meaning that the home may have preexisting

title defects unknown to the borrower.

30

30

See Grant S. Nelson, The Contract for Deed as a Mortgage: The Case for the Restatement Approach, 1998 B.Y.U.

L . Rev. 1111, 1143 (1998) (“Because there is normally no third party lender to insist on a title examination, the

vendor has no incentive to have his or her own title examined.”); Battle, supra note 11, at 8 (“Title problems are

extremely common in land contract transactions. Advocates report that contract sellers often fail to disclose liens

and mortgages that exist at the time the contract is entered into.”); FHCCI, supra note 10, at 10 (“However, a simple

warranty of title from the seller does not provide the buyer with the same protections that they would have under a

traditional mortgage, where the lender would require the buyer to purchase title insurance. Title insurance provid es

a thorough check for contesting title claims, which allows the buyer to back out of the sale if it turns out that, f or

example, a previous owner left a lien on the property or had a disputed will. After the sale, title insurance als o

insures the buyer (and the mortgage lender) from any financial losses that come from a contested title.”).

The borrower may also be unaware of any liens

imposed on the property during the course of the contract.

31

31

See Way, supra note 28, at 138 (“Because so many installment contracts are never recorded, informal buyers are

particularly vulnerable to title defects arising after the transaction is initiated.”); David Migoya, Buyers Pay Taxes

Twice or Risk Losing Homes, Belleville News-Democrat (Illinois) (May 17, 1993), at 1A.

Thus, it can be difficult for

borrowers to eventually obtain legal title to the home, even if they are able to make all of the

payments due under the contract for deed.

In addition to these consumer harms, contracts for deed can harm an entire community. High

default rates reduce the home values of surrounding homes, increase the insurance rates, and

create safety and public health risks from empty or dilapidated homes. Contracts for deed can

harm a community by financing the repeated flipping of perpetually substandard housing stock.

The prevalence of contract for deed sellers in low-income communities concentrates such harms

on these communities.

12 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

3. The history of predatory

contracts for deed

From the 1930s through the 1960s, Black borrowers in the United States were largely excluded

from the mainstream home-mortgage market due to discrimination. Maps produced by the

government drew red lines around any neighborhood that was not majority white.

32

32

Patrice Alexander Ficklin & Charles Nier III, Poverty & Race Research Action Council Racial Justice in Housing

Finance: A series on New Directions, The Use of Special Purpose Credit Programs to Promote Racial and

Economic Equity, 52, 54-55 (May 2021),

https://www.prrac.org/pdf/racial-justice-in-housing-finance-series-

2021.pdf; see also Amy Hillier, Redlining And The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, 29 J. Urb. Hist. 394-395

(2003); Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Case for Reparations, The Atlantic (June 2014),

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

The practice

of redlining was institutionalized by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC).

33

33

Ficklin & Nier, supra note 32, at 54.

Established in 1933 during the Great Depression to assist distressed homeowners, the HOLC

developed a grading system to assess neighborhood risk across the United States.

34

34

Id.

In 1934, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured private

mortgages, causing a drop in interest rates and a decline in the size of the down payment

required to purchase a house.

35

35

Coates, supra note 32; Ficklin & Nier, supra note 32, at 55.

Building on the HOLC’s rating system, the FHA developed its

own guidance on race and real estate values. For example, the FHA Underwriting Manual

recommended restrictive covenants as a method to maintain neighborhood stability via racial

segregation.

36

36

Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, 208 (1985).

Driven by these federal housing policies, private lenders regularly refused loans to homebuyers

in Black neighborhoods while underwriting the construction of homes by whites of a similar

economic status a few blocks away.

37

37

Id. at 208-209.

Black borrowers were often left with contracts for deed as

the only alternative to finance a home purchase. One study found that borrowers in contract for

deed sales paid an average of 84 % more than the speculator’s purchase price on the home and

13 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

that “between 75 percent and 95 percent of the homes sold to black families [in Chicago] during

the 1950s and 60s were sold on contract.”

38

38

The Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University, The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago:

New Findings on the Lasting Toll of Predatory Housing Contracts, iii (May

2019), https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Plunder-of-Black-Wealth-in-Chicago.pdf.

The combination of high housing prices and above-market interest rates meant that contract

holders had to make large monthly payments to meet their debt obligations. If they defaulted,

speculators evicted them and quickly offered the house to another Black borrower. The

arrangement brought speculators a profit with relatively little risk.

39

39

Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton University

Press (rev. ed. 2005).

A secondary market for

installment contract paper provided liquidity to the market and provided sellers with capital to

sustain the practice. Speculators and investors could recoup their entire investment within just

two years.

40

40

Arnold Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race & Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960 (1998).

Since contracts for deed did not require appraisals or inspections, sellers sometimes sold

dilapidated yet high-priced homes to Black borrowers. The absence of loss mitigation or

workout options meant that when borrowers fell behind on their payments, they were evicted

without foreclosure proceedings, losing all equity in their homes.

41

41

Stacy Purcell, The Current Predatory Nature of Land Contracts and How to Implement Reforms, 93 Notre Dame

L . Rev. 1771, 1774 (2018).

Even if borrowers

successfully made payments over the full term of their contracts, they could lose everything at

the end of the term due to balloon payments that borrowers could not finance.

42

42

Beryl Satter, Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (2010). See also

Minneapolis Fed, supra note 16.

For a more detailed discussion of history related to predatory contracts for deed, see Appendix

A.

14 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

4. Investors fueled a

resurgence in contracts for

deed

The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis and ensuing Great Recession led to a surge in contracts for

deed.

43

43

Purcell, supra note 41, at 1775.

Foreclosures rose during the crisis, tripling from 2006 to 2008.

44

44

See Rakesh Kochhar, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, & Daniel Dockterman, Through Boom and Bust: Minorities,

Immigrants and Homeownership, Pew Hispanic Center, ii (May 12, 2009),

https://search.issuelab.org/resources/11405/11405.pdf

.

By 2010, 4.6% of home

mortgage loans were in foreclosure, with low-income and other underserved and underinvested

communities hardest hit.

45

45

See Adalberto Aguirre, Jr. & Ruben O. Martinez, The Foreclosure Crisis, the American Dream, and Minority

Households in the United States: A Descriptive Profile, 40 Social Justice 6, 7-9 (2013),

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24361645

(“By 2010… 4.6 percent of home mortgage loans were in foreclosure (US

Census Bureau 2012)”); see also Table 1193. Mortgage Originations and Delinquency and Foreclosure Rates: 1990

to 2009, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2010/compendia/statab/130ed/tables/11s1193.pdf.

As borrowers defaulted on their loans, ownership of homes reverted

to mortgage lenders, swelling their portfolios of real estate owned (REO) properties with

concentrations of REO in communities experiencing rapid declines in property values. Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac (federal government-sponsored enterprises that buy and guarantee

mortgages) responded to the rise in their REO assets by scaling up their disposition processes,

selling these properties in bulk at a discount.

46

46

See Goldstein & Stevenson, supra note 10.

Investors began purchasing tens of thousands of

these foreclosed homes. As a share of nationwide home sales, activity by these investors

increased more than six times between 2004 and 2012.

47

47

Business investors buying three or more homes accounted for almost 6.5% of home sales in 2012, up from less than

1% in 2004. Raven Molloy & Rebecca Zarutskie, Business Investor Activity in the Single-Family-Housing Market,

Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Reserve Sys. FEDS Notes (Dec. 5, 2013),

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2013/business-investor-activity-in-the-single-

family-housing-market-20131205.html.

Investment firm Harbour Portfolio

15 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Advisors (Harbou

r), for example, bought 6,700 single-family homes in the aftermath of the

2008 economic collapse, spending an average of $8,000 per home.

48

48

Alexandra Stevenson & Matthew Goldstein, Wall Street Veterans Bet on Low-Income Home Buyers, N.Y. Times

(Apr. 17, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/18/business/dealbook/wall-street-veterans-bet-on-low-

income-homebuyers.html; Matthew Goldstein & Alexandra Stevenson, Cincinnati sues Seller of Foreclosed Homes,

Claiming Predatory Behavior, N.Y. Times (Apr. 20, 2017),

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/20/business/dealbook/cincinnati-sues-harbour-seller-foreclosed-homes.html;

Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 4.

Some i

nvestors were aware that many potential borrowers were struggling. Millions of

consumers nationwide faced increased barriers to credit access with newly damaged credit

records.

49

49

See Wei Li, Laurie Goodman, & Denise Bonsu, Widespread credit blemishes may well be holding back our

economic recovery, Urban Institute (Nov. 1, 2016), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/widespread-credit-

blemishes-may-well-be-holding-back-our-economic-recovery.

Aspiring homeowners blocked from the conventional mortgage market became

targets for investment firms like Harbour and Shelter Growth Capital (run by the former head of

Goldman Sachs mortgage department) that sought to profit from their newly acquired housing

stock via contracts for deed.

50

50

Alexandra Stevenson & Matthew Goldstein, Wall Street Veterans Bet on Low-Income Home Buyers, N.Y. Times

(Apr. 17, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/18/business/dealbook/wall-street-veterans-bet-on-low-

income-homebuyers.html; Ann Carpenter, Abram Lueders, & Chris Thayer, Informal Homeownership Issues:

Tracking Contract for Deed Sales in the Southeast (Atlanta Fed Report), Fed. Reserve Bank of Atlanta, 5 (2017),

https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/community-development/publications/discussion-

papers/2017/02-informal-homeownership-issues-tracking-contract-for-deed-sales-in-the-southeast-2017-06-

14.pdf.

At least some investors marketed to former homeowners who

sought to regain their homes after losing them in foreclosure by selling their homes back to

them on usurious terms, which included using contracts for deed in some cases.

51

51

See e.g., Hodges, et al., v. Swafford, 863 N.E.2d 881, 883-892 (Ind. Ct. App. 2007) (Court found that lender

violated the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) when the lender purchased the borrower’s home who was facing

impending foreclosure and subsequently resold the home back to the borrower via a land contract).

Resear

chers have documented the rise of contracts for deed in various parts of the country

following the 2008 financial crisis. For the last year it was collected, American Housing Survey

data indicated that 3.5 million owner-occupied households had a contract for deed in 2009,

representing 4.6% of all owner-occupied households.

52

52

Atlanta Fed Report, supra note 50, at 6. These numbers may be understated given the various terms used for

contracts for deeds (i.e., land installment contracts), the challenge that borrowers may not understand that they do

not have a mortgage when they completed the survey, and the high degree of overlap across populations that are

undercounted in census data and are contract for deed borrowers. See e.g., Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 2

(“Reliable data about the prevalence of land contract sales is not readily available. According to the U.S. Census, 3.5

million people were buying a home through a land contract in 2009, the last year for which such data is available …

But this number likely understates the prevalence of land contracts, as many contract borrowers do not understand

the nature of their transaction sufficiently to report it.”); FHCCI, supra note 10, at 5 (challenges in examining the

use of land contracts include the lack of comprehensive public data on land contracts and the expectation of a high

number of unrecorded land contracts).

A study examining tax records in several

16 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

major cities found that contracts for deed increased from 2008 to 2013.

53

53

See Atlanta Fed Report, supra note 50, at 9-10.

A nationally

representative survey conducted by Pew in 2021 showed that approximately 8 million

Americans have used a contract for deed at some point, amounting to 5% of consumers who

borrowed to buy a home.

54

54

The Pew Charitable Trusts, Millions of Americans Have Used Risky Financing Arrangements to Buy Homes (May

23, 2022), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/04/millions-of-americans-

have-used-risky-financing-arrangements-to-buy-homes (last visited July 3, 2024) and The Pew Charitable Trusts,

Senate Eyes Land Contract Risks, Opportunities (July 11, 2023), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-

analysis/speeches-and-testimony/2023/07/11/senate-eyes-land-contract-risks-opportunities (last visited July 12,

2024).

About 15% of homeowners with contracts for deed were Black and

13% were Hispanic.

55

55

The Pew Charitable Trusts, Senate Eyes Land Contract Risks, Opportunities (July 11, 2023),

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/speeches-and-testimony/2023/07/11/senate-eyes-land-

contract-risks-opportunities (last visited July 12, 2024).

The post-Great Recession experiences of communities in Atlanta,

Minneapolis, Detroit, and the Texas border colonias highlight the impact of contracts for deed

on those communities.

4.1 Atlanta

Harbour purchased homes foreclosed during the 2008 mortgage collapse, including hundreds in

Atlanta.

56

56

See Goldstein & Stevenson, supra note 10.

There, Harbour marketed the homes, often priced between $40,000 and $50,000, to

low-income Atlanta borrowers using contracts for deed.

57

57

Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 4-5; Atlanta Legal Aid, 2018: Harbour Portfolio,

https://atlantalegalaid.org/portfolio-item/2018-harbour-portfolio/.

In 2018, Atlanta Legal Aid sued Harbour on behalf of Black homebuyers claiming that it charged

exorbitant interest rates, and forced borrowers to make needed repairs to the dilapidated

properties that were uninsurable due to their defects.

58

58

Atlanta Legal Aid, supra note 57.

Plaintiffs claimed that Harbour then

evicted borrowers if they missed a payment or were not able to make needed repairs, forfeiting

all money payments made to that point, including the value of any repairs the borrower had

made.

59

59

Third Amended Complaint, Horne, et al., v. Harbour Portfolio, VII, LP., et al., No. 1:17-CV-954-RWS, at ¶¶ 57-62

(N.D. GA May 18, 2018).

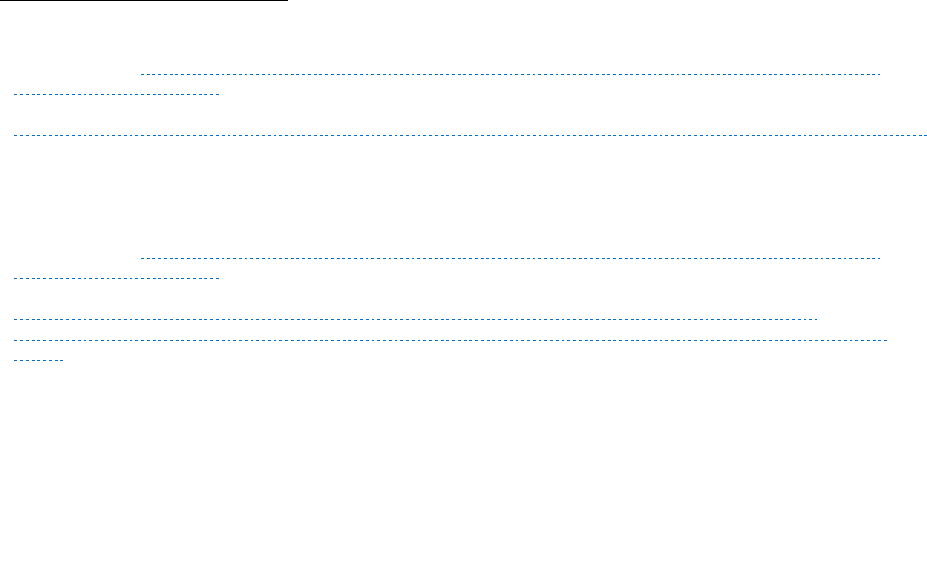

As depicted in Figure 1 below, National Consumer Law Center research found that—

despite Atlanta being only 32.1% Black—84% of Harbour Portfolio properties were located in

17 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

majori

ty Black census blocks.

60

60

Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 5.

In 2019 the case settled, and Atlanta Legal Aid recovered actual

damages and restructured mortgages for their clients.

61

61

Order, Horne, et al., v. Harbour Portfolio VII, LP, No. 1:17-CV-954-RWS (N.D. GA Jan. 7, 2019); Atlanta Legal Aid,

supra note 57.

FIGURE 1: HARBOUR PORTFOLIO PROPERTIES AND MAJORITY BLACK CENSUS BLOCKS

4.2 Minneapolis

In Minneapolis, contract for deed sales increased 50 % from 2008 to 2013.

62

62

See Meitrodt, supra note 10.

Some observers

have indicated that most of those contracts were designed to fail.

63

63

Id.

After a subsequent decline in

18 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

contracts for deed in the area, they have experienced a resurgence. In 2021, more than 1,800

contracts for deed were signed in Minnesota’s 11 most populous counties, which included

Minneapolis and St. Paul.

64

64

See Jessica Lussenhop, Joey Peters, & Haru Coryne, Real Estate Investors Sold Somali Families on a Fast Track to

Homeownership in Minnesota. The Buyers Risk Losing Everything, ProPublica (Nov. 21, 2022),

https://www.propublica.org/article/how-contracts-for-deed-put-families-at-financial-risk.

Some contract for deed providers targeted Muslim borrowers, including particularly those in the

Somali community. For Minnesota’s Somali community, which numbers around 80,000,

homeownership may require compliance with religious law, which normally forbids both the

charging and paying of interest. Some lenders have marketed contracts for deed to potential

borrowers of Somali descent as way to purchase a home without a mortgage that carries

interest—when the contracts actually contain hidden interest. Contracts for deed are advertised

to the Somali community, in both English and Somali, with messages that include: “Buying a

house in the States normally asks you to pay interest. Or to have a good credit score. But you

don’t have to if you choose a contract-for-deed agreement.”

65

65

Id.

In May 2024, the Minnesota

Attorney General filed suit against a group of companies, alleging that collectively they violated

state and federal law by selling houses via predatory and illegal contracts for deed, used

deceptive trade practices to market their contracts for deed, and discriminated by offering unfair

terms to Muslim borrowers.

66

66

The Office of Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, Attorney General Ellison sues home seller and lender for

predatory lending, deceptive practices, and religious discrimination (May 14, 2024),

https://www.ag.state.mn.us/Office/Communications/2024/05/14_Banken.asp

.

The Attorney General recently described contracts for deed as “a

poor man’s mortgage that combine all the responsibilities of homeownership with all the

disadvantages of renting, while offering the benefits of neither.”

67

67

The Office of Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, Attorney General Ellison warns Minnesotans to avoid

contract for deed pitfalls and scams (May 29, 2024),

https://www.ag.state.mn.us/Office/Communications/2024/05/29_ContractForDeed.asp

.

4.3 Detroit

In Detroit, one estimate found more contracts for deed were executed in 2015 than mainstream

mortgages.

68

68

Joel Kurth, Land contracts trip up Would-be homeowners, The Detroit News (Feb. 29, 2016) (comparing Wayne

County property records with RealtyTrac data), https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-

city/2016/02/29/land-contracts-detroit-tax-foreclosure-joel-kurth/81081186/.

Based on their experience defending borrowers in eviction cases, advocates

observed that contracts for deed often involved substandard housing conditions, including

19 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

homes lacking heating, hot water, and plumbing,

69

69

Id.

sometimes with an outstanding tax bill, all of

which contributed to the occupants being unable to make the payments and losing their

homes.

70

70

Akers & Seymour, supra note 29, at 135.

In one case, for example, a contract for deed borrower agreed to pay $43,003 for the

home with an 11% interest rate. The monthly payment was $400 for principal and interest and

$170 for property taxes. The borrower was eventually evicted and lost all equity in the home,

including approximately $12,000 in payments.

71

71

Id. at 134.

Other research has indicated a general lack of standard mortgage credit available for smaller

loan amounts in the Detroit area where contracts for deed were often found, reflecting the

impact of the failure of banks and savings associations to adequately serve low-income

communities.

72

72

Ann Carpenter, Taz George, & Lisa Nelson, The American Dream or Just an Illusion? Understanding Land

Contract Trends in the Midwest Pre- and Post-Crisis, Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies 13-14

(2019) (finding little overlap at lower sale prices between HMDA-reported loans and contract for deed amounts for

which about half in Wayne County sold below $50,000),

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media/imp/harvard_jchs_housing_tenure_symposium_carpent

er_george_nelson.pdf.

4.4 Texas Border Colonias

Many landowners and developers in the colonias situated near the Texas-Mexico have offered

property financing using contract for deed loans.

73

73

Fed. Reserve Bank of Dall. (Dall. Fed Report), Las Colonias in the 21

st

Century: Progress Along the Texas-Mexico

Border, 6 (April 2015), https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/cd/pubs/lascolonias.pdf. There are seller-

financing entities in Texas that offer contracting agreements that are not traditional contracts for deed but contain

some of the same features of contracts for deed that result in harm to consumers.

As noted above, contract for deed loans

would not require the seller to provide proof of a clear title, ensure the presence of needed

infrastructure, or guarantee that existing structures on the land meet county building codes.

74

74

Id.

Comparisons between Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data and Census Bureau

American Community Survey (ACS) data demonstrate a low level of mainstream HMDA home

purchase lending in the HMDA data for Texas counties where contracts for deed or other

20 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

a

lternative financing arrangements exist.

75

75

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Table B25081: Mortgage Status (providing county-level

statistics grouping together housing debt for the category “mortgage, contract to purchase, or similar debt”),

available at US Census Bureau, Table B25081: Mortgage Status,

https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT1Y2021.B25081. While the HMDA data do not include contracts for deed, the

ACS variable shown in the above table includes both mortgages and contracts for deed, so a low ratio means that

there is a low level of HMDA purchase loans compared to the number of housing units with a mortgage or contract

for deed.

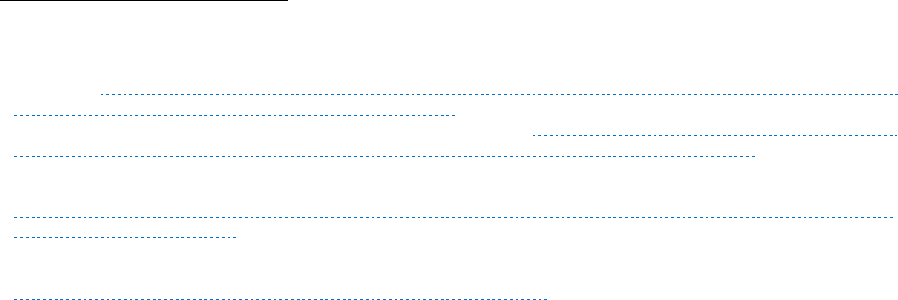

The table below provides a comparison between

HMDA reported home purchase mortgage originations (data that would exclude contracts for

deed or other alternative financing arrangements) and ACS data on housing units with a

mortgage, contract to purchase or similar debt in (1) Hidalgo County, Texas, the single county

with the largest number of colonias in the country; (2) the group of six counties, all in Texas,

with the highest concentration of colonias in the country;

76

76

Dall. Fed Report, supra note 73, at 1.

(3) all of Texas; and (4) the entire

country.

TABLE 2: ACS HOUSING UNITS WITH A MORTGAGE, CONTRACT FOR DEED, OR SIMILAR DEBT VS

HMDA PURCHASE ORIGINATIONS, 2017/18 TO 2021/22

Hidalgo

County

Colonias

Counties

All Texas National

ACS Housing Units with a Mortgage,

Contract for Deed, or Similar Debt

70,433 238,215 3,640,097 49,759,315

HMDA Purchase Originations (Mainstream

Mortgage Only)

24,276 97,945 1,990,539 21,690,628

Ratio (HMDA to ACS)

0.34 0.41 0.55 0.44

Note that, due to data access considerations and a change in HDMA reporting thresholds, ACS data covers years

2017-2021, while HMDA data covers 2018-2022.

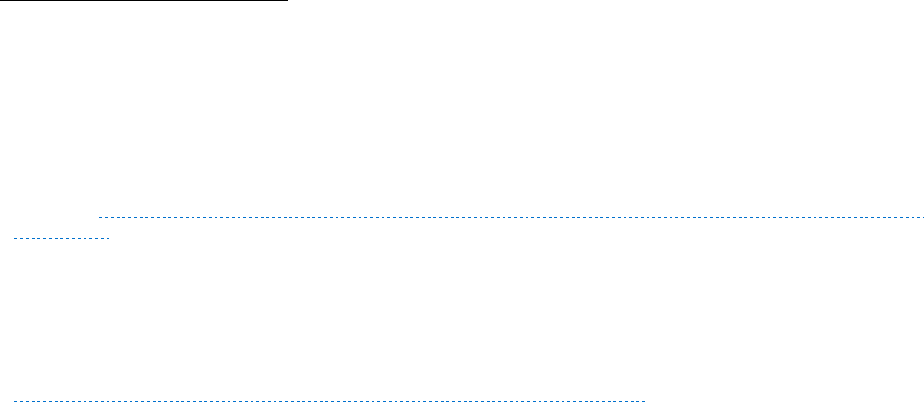

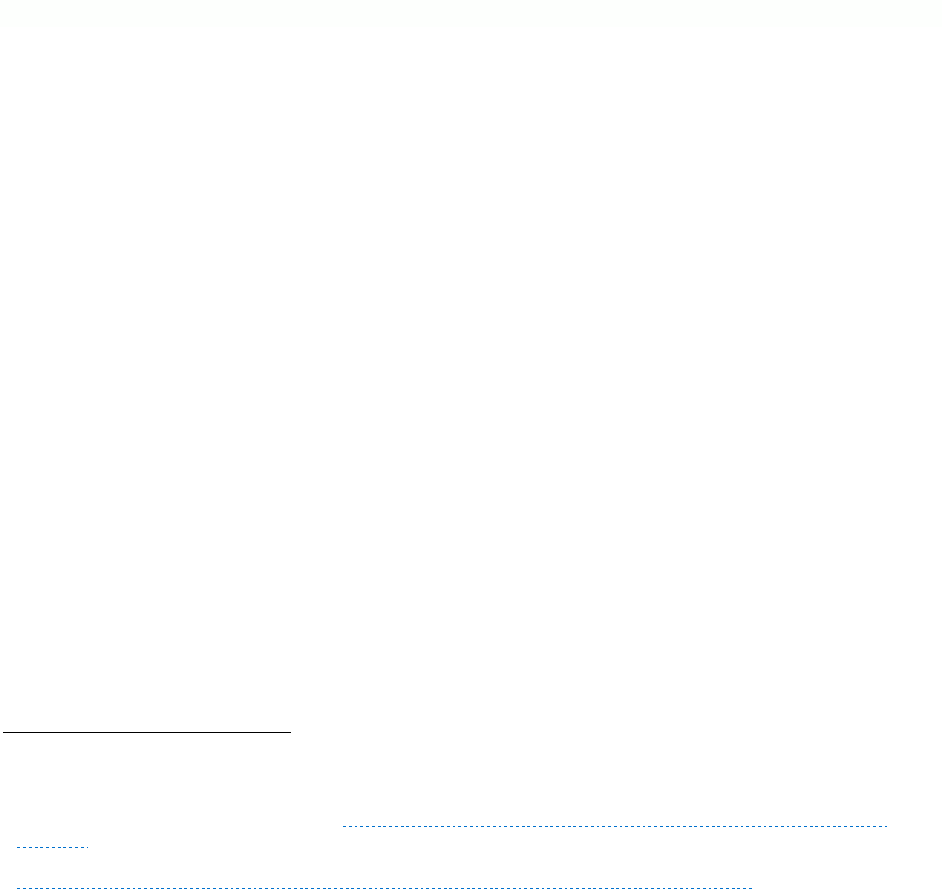

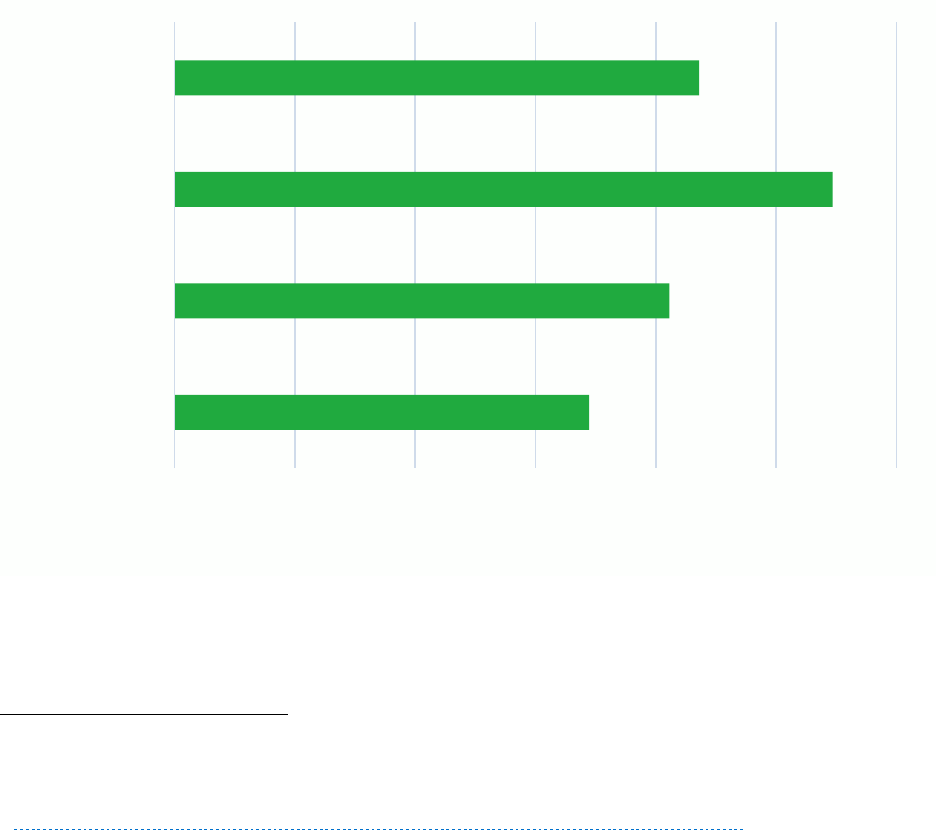

The graph below plots the same data for the six Texas counties with the highest number of

colonias. The graph shows that, on average, these counties have relatively low rates of HMDA

21 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

h

ome purchase mortgage lending activity per housing unit with a mortgage when compared to

all of Texas and nationally.

77

77

Research from the Housing Assistance Council shows a similar relationship for all mortgage lending and owner-

occupied housing units. Housing Assistance Council, Colonias Investment Areas: Working Toward a Better

Understanding of Colonia Communities for Mortgage Access and Finance, 30-33 (November 2022),

https://ruralhome.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/colonias-investment-areas-report.pdf.

These counties contain large Hispanic populations.

78

78

See FHCCI, supra note 10, at 14 (targeting of Hispanic and immigrant communities with contracts for deed or other

similar alternative financing arrangements occurs in other parts of the country such as Indiana: “some land contract

companies hire Spanish-speaking staff to communicate with consumers. Using a Spanish-speaking intermediary is

a key tool in building trust with Spanish-speaking consumers. These consumers may prefer to work with a real

estate agent or employee that speaks their language, allowing them to feel comfortable and avoid

miscommunication during translations. However, if the consumer does not receive an explanation of the

transaction and a translation of the documents from an independent party, they become totally reliant on the word

of the Spanish-speaking real estate agent or employee, who has a vested interest in persuading them to take part in

the land contract.”).

FIGURE 2: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HMDA AND HOUSING DATA

0.34

0.41

0.55

0.44

0.00 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.40 0.50 0.60

Hidalgo County

Colonias Counties

All Texas

National

HMDA Purchase Originations/ACS Housing Units with a Mortgage, Contract for

Deed, or Similar Debt

22 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

5. Contract for deed sellers

may exploit—and

perpetuate—market

distortions

Beyond the risks contracts for deed pose to individual borrowers, these loans may also exploit

and perpetuate distortions in the housing market more broadly. Data on the prevalence of

contracts for deed in underserved communities support an inference that the dearth of

traditional sources of funding for home purchases creates market conditions that can drive

borrowers to contracts for deed and other alternative funding arrangements.

79

79

See Atlanta Fed Report, supra note 50, at 13.

At the same time,

contract for deed sellers may exploit borrowers in underserved “credit deserts.” Indeed, just as

contract for deed sellers did historically, some contract for deed sellers and investors today

appear to target communities with low credit access. Research has found that contract for deed

properties purchased by investors tend to be located in neighborhoods with fewer bank

branches per capita than the surrounding metropolitan average.

80

80

Id.

Lack of mainstream mortgage options can be particularly acute for lower-cost homes, where

research suggests greater concentration of alternative financing, including contracts for deed.

Research indicates that of “the single-family homes sold in 2015 in the United States, 14 percent,

or 643,000 homes, sold for $70,000 or less, of which slightly more than one-fourth were

financed with a mainstream mortgage loan product.”

81

81

Alanna McCargo, Bing Bai, Taz George, & Sarah Strochak, Small-Dollar Mortgages for Single-Family Residential

Properties, Urban Institute, 1 (April 2018),

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98261/small_dollar_mortgages_for_single_family_residen

tial_properties_2.pdf.

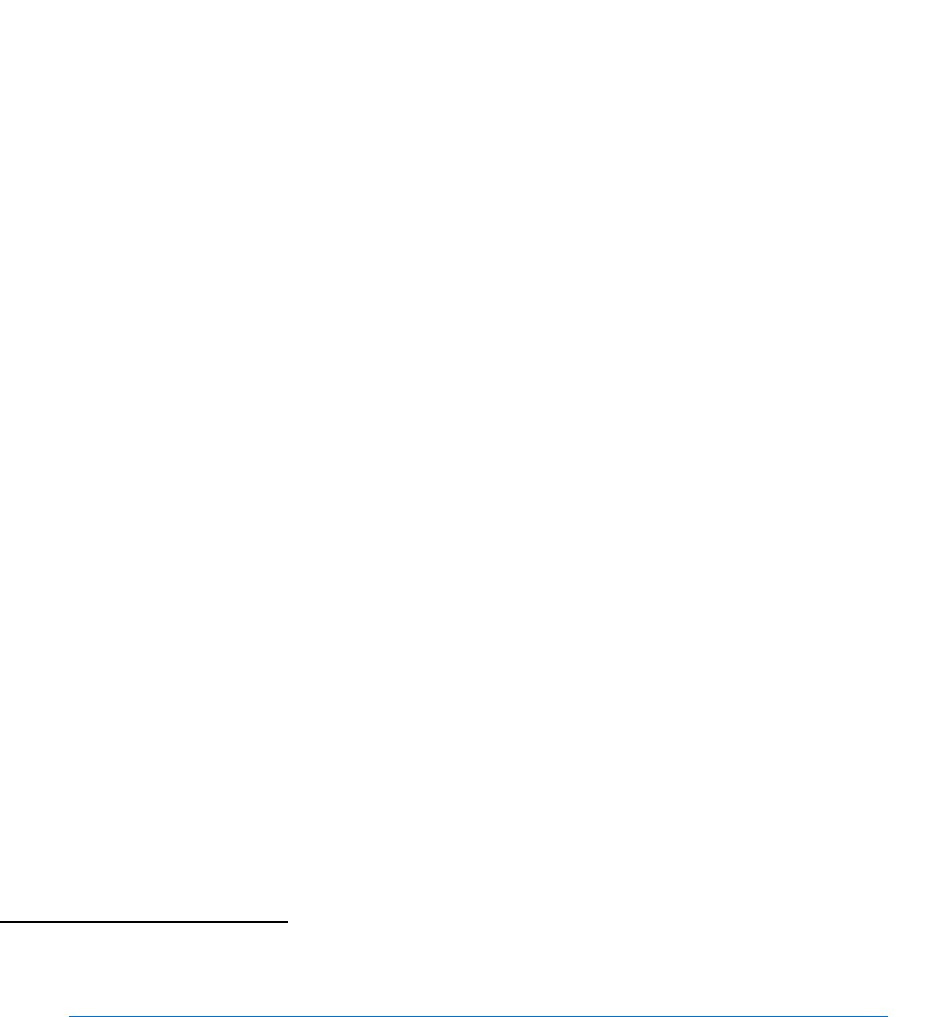

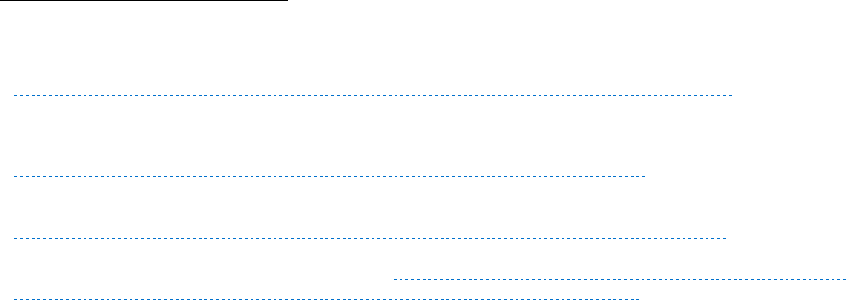

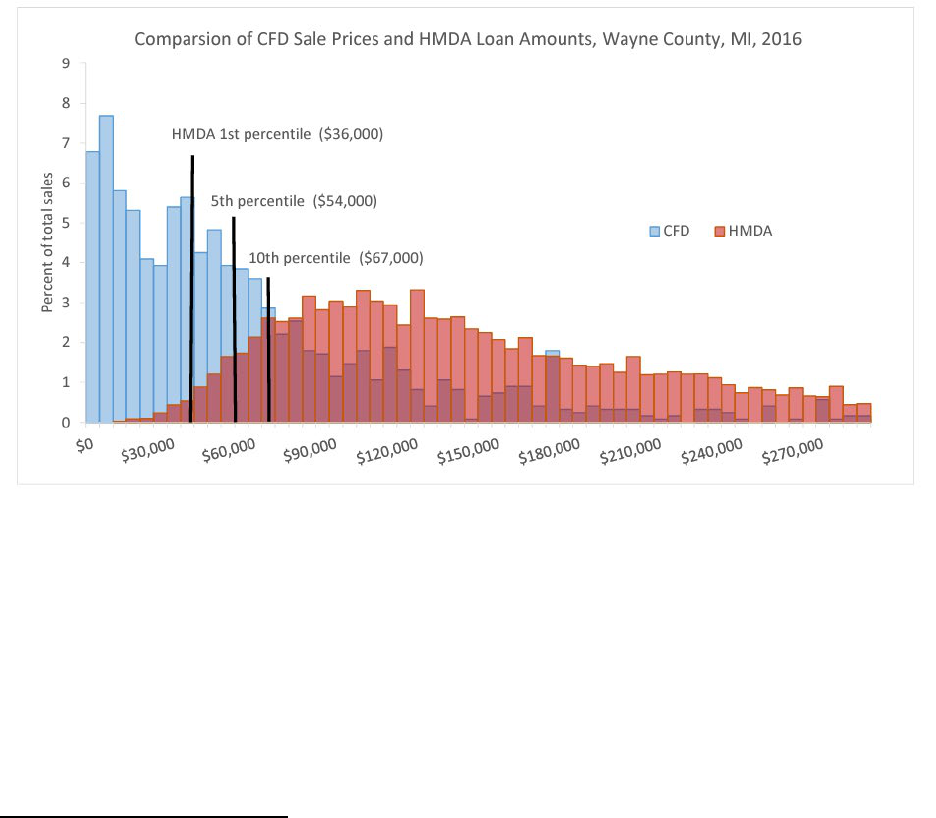

As depicted in Figure 3, below,

researchers found that in Wayne County, Michigan, few lower-priced home sales appear in

HMDA data, which is an indication that those homes are more likely to have been purchased

23 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

with alternative financing due to the lack of traditional credit options for smaller dollar

loans.

82

82

See Carpenter, et al., supra note 72, at 13-14 (analyzing data on loan amounts of $53,000 or less).

FIGURE 3:

COMPARISON OF CFD SALE PRICES AND HMDA LOAN AMOUNTS, WAYNE COUNTY, MI, 2016

The market impact of targeting communities with contracts for deed may be worsened by the

purchasing power some investors have, allowing them to acquire relatively low-cost housing

stock in bulk and thereby control housing options for lower-income borrowers.

83

83

See Purcell, supra note 41, at 1776-1777 (“land contracts give these investors the freedom to structure deals to their

advantage and allow them to sell to people who may be eager to own a home, but are unable to get a bank-financed

mortgage.”).

Once contracts

for deed take root in a community, they can harm the housing market as a whole by contributing

to below standard homes, inflated home prices, and less access to mainstream mortgage credit.

The use of contracts for deed can create and perpetuate substandard housing stock because, as

noted above, sellers are able to generate profit even without maintaining the property by

repeatedly selling the property to maximize profits.

84

84

See generally Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 8 (“Land installment contract transactions are structured to fail.

Sellers profit by churning a house through one land contract buyer after another. Sellers take whatever down

payment the would-be owner can afford, pull in their payments and sweat equity for as long as possible, and then

evict them and cycle another buyer into the property.”).

Borrowers are motivated to improve their

24 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

p

roperties but may not have the financial resources to do so because they do not have access to

traditional financing such as home equity loans. This is because borrowers do not attain legal

title to the properties nor build equity in the properties when they enter into contracts for deed,

unlike with mainstream mortgages.

85

85

Id. at 3 (investors “reap substantial profits, at the expense of would-be homeowners who, because of the structure

of the transaction, build no equity in the property, despite their payments.”).

Repeatedly selling properties at inflated prices also drives up housing prices across the market

overall.

86

86

See id. at 8 (“[t]he purchase price in a land contract often, although not always, greatly exceeds the fair market

value of the home.”).

One observer noted that “[m]any of the homes sold through land contracts come with

huge mark-ups built into the price. It is not uncommon to see an investor purchase a home at

auction for $5,000 and sell it days later on land contract (with no repairs) for $30,000.”

87

87

See e.g., Battle, et al., supra note 11, at 3.

Properties sold via contracts for deed may also be unmarketable. This could be due to title

defects discussed above. In addition, properties being flipped by contract for deed sellers are not

available to be purchased via mainstream mortgage financing, further distorting housing and

credit markets.

25 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

6. Conclusion

The set-up-to-fail nature of many contracts for deed harms borrowers and communities. Sellers,

who may profit from repeated flipping of the property, may not disclose all of the costs of the

transaction, assess the borrower’s ability to repay, or offer any loss mitigation options for

borrowers who are unable to make timely payments.

Enforcement of existing legal protections can play a role in addressing many of the most

harmful practices. As previously mentioned, several federal laws under the CFPB’s jurisdiction

provide consumer protections that address harms that often result from predatory contract for

deed lending. Several of these legal provisions allow borrowers to bring private lawsuits, and

state attorneys general also have authority to enforce these laws as well as relevant state and

local laws. The CFPB will continue to utilize its authorities to address contract for deed loans

that may set up borrowers to fail. The CFPB will also carefully review any whistleblower leads

and relevant consumer complaints to continue to study and evaluate contracts for deed.

26 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

APPENDIX A: THE HISTORY OF PREDATORY

CONTRACTS FOR DEED

From the 1930s through the 1960s, Black borrowers in the United States were largely excluded

from the conventional home-mortgage market due to discrimination. Maps produced by the

government drew red lines around any neighborhood that was not majority white.

88

88

Ficklin & Nier, supra note 32, at 54-55; Hillier, supra note 32, at 394-395; Coates, supra note 32.

While

discrimination against Black borrowers was common, the practice of redlining was

institutionalized by the HOLC.

89

89

Ficklin & Nier, supra note 32, at 54.

Established in 1933 during the Great Depression to assist

distressed homeowners, the HOLC developed a grading system to assess neighborhood risk

across the United States.

90

90

Id.

The HOLC’s grading system was based upon information obtained in a City Survey Program

which distributed surveys to real estate professionals and lenders that included explicit

questions regarding racial composition of neighborhoods.

91

91

Hillier, supra note 32, at 394-395; Jackson, supra note 36, at 197.

HOLC then established four color-

coded categories of quality that eventually became “residential security” maps that reflected the

various grades.

92

92

Hillier, supra note 32, at 394-395.

The maps subdivided metropolitan areas into sections ranked from A (green)

through D (red), based on factors that included the age of buildings, their condition, and the

amenities and infrastructure in the neighborhood. Most important in determining a

neighborhood’s risk classification was the level of racial, ethnic, and economic homogeneity: the

absence or presence of “a lower grade population.”

93

93

Sugrue, supra note 39.

Detroit serves as an example of the historical lending discrimination experienced by Black

borrowers.

94

94

Id. at 101.

Every Detroit neighborhood with a Black population was rated “D,” or “hazardous”

by federal appraisers, and colored red on the HOLC Security Maps.

95

95

Id.

Areas where there was

“shifting” or “infiltration” of “an undesirable population” were given “D” ratings.

96

96

Id.

While the

HOLC had a mixed record of lending in “C” and “D” neighborhoods, perhaps its greatest impact

27 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

was placing the federal government’s seal of approval on the linkage between real estate value

and race and its influence on the FHA.

97

97

Ficklin & Nier, supra note 32; see also Hillier, supra note 32, at 398.

In 1934, Congress created the FHA, which insured private mortgages, causing a drop in interest

rates and a decline in the size of the down payment required to purchase a house.

98

98

Coates, supra note 32.

Building on

the HOLC’s rating system, the FHA developed its own guidance on race and real estate values.

For example, the FHA Underwriting Manual warned of the dangers of “infiltration of

inharmonious racial groups and nationality groups.” To prevent such “infiltration,” the manual

recommended restrictive covenants as a method to maintain neighborhood stability via racial

segregation.

99

99

Jackson, supra note 36, at 208.

Driven by these federal housing policies, private lenders regularly refused loans to homebuilders

in Black neighborhoods while underwriting the construction of homes by whites of a similar

economic status a few blocks away.

100

100

Id. at 208-209.

Thus, while new federal policies placed homeownership

within reach for many white working families, the FHA and other federal housing policy

officially promoted real estate sales and bank lending practices that discriminated against

prospective Black borrowers.

101

101

Coates, supra note 32.

Given the lack of access to traditional forms of credit, Black borrowers were often left with

contracts for deed as the only alternative to finance a home purchase. Typically, speculators

offered contracts for deed to Black borrowers that included high down payments and sometimes

high interest rates. One study found that borrowers in contract for deed sales paid an average of

84% more than the speculator’s purchase price on the home and that “between 75 percent and

95 percent of the homes sold to black families [in Chicago] during the 1950s and 60s were sold

on contract.”

102

102

The Samuel DuBois Cook Center, supra note 38.

The combination of high housing prices and above-market interest rates meant

that contract holders had to make large monthly payments to meet their debt obligations. If they

defaulted, speculators evicted them and quickly offered the house to another Black borrower.

The arrangement brought speculators a profit with relatively little risk.

103

103

Sugrue, supra note 39.

A secondary market

for installment contract paper provided liquidity to the market and provided sellers with capital

28 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

to sustain the practice. Speculators and investors could recoup their entire investment within

just two years.

104

104

Hirsch, supra note 40.

Black newspapers often included property advertisements that listed low down payments but

not total sales price – a clear indicator that the property was being sold on contract and targeted

to Black potential borrowers.

105

105

Satter, supra note 42.

Since contracts for deed did not require appraisals or

inspections, sellers sometimes sold dilapidated yet high-priced homes to Black borrowers. The

absence of loss mitigation or workout options meant that when borrowers fell behind on their

payments, they were evicted without foreclosure proceedings, losing all equity in their homes.

106

106

Purcell, supra note 41, at 1774.

Even if borrowers successfully made payments over the full term of their contracts, they could

lose everything at the end of the term due to balloon payments that borrowers could not

finance.

107

107

Satter, supra note 42. See also Minneapolis Fed, supra note 16.

The story of the James family in Chicago provides an example of the predatory

practices associated with certain contracts for deed.

108

108

Satter, supra note 42. The following is a condensed version of an account provided in Satter.

29 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

In August 1955, the James family purchased a home on contract in Chicago for

$13,500 from Charles Peters, a real estate speculator who had purchased the

home just 13 days earlier for $8,000. The James’ contract required a down

payment of $1,000 and monthly payments of $105 over a 3-year term, with a

f

inal balloon payment of $10,500 which Peters said he would help them to

finance. Peters explained he was offering them the deal because they might have

troubles “because [they were] colored.”

Af

ter one year, Peters sold the contract at a discount to Arthur Krooth, a liquor

store owner. When the end of the contract neared, the James family sought

Peters’ promised assistance to finance the balloon payment. Peters responded

he could care less what happened to them because he no longer owned the

home. The James family tried to secure a mortgage to finance the balloon

payment, but their applications were denied by six banks because the property

was not worth the $10,500 needed for the balloon payment. Thereafter, the

James family was evicted and lost all the money they had spent on their home,

including improvements made to it during the term of the contract.

The James family was not alone in their struggle to attain homeownership in Chicago. As in

other cities, housing discrimination was common. White neighborhoods formed block

associations to ensure segregation. They urged other whites not to sell to Blacks and pressured

Blacks who did manage to buy to sell their properties back to whites. Some white residents

resorted to violence, including bombings, to keep their neighborhoods segregated.

109

109

Coates, supra note 32. (“On July 1 and 2 of 1946, a mob of thousands assembled in Chicago’s Park Manor

neighborhood, hoping to eject a black doctor who’d recently moved in. The mob pelted the house with rocks and set

the garage on fire. The doctor moved away.”).

Blockbusting was also common—where speculators convinced whites to sell their homes out of

fear the neighborhood was becoming desegregated, and then profited by selling those properties

to Black buyers.

110

110

Blockbusting is a form of housing discrimination that was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 that

encourages homeowners to sell their property based on fears of an influx of non-white residents. 42 U.S.C. §

3604(e) (2018); see, e.g., Satter, supra note 42.

In the segregated neighborhoods of Chicago, contracts for deed became a common form of

financing for Black borrowers. One estimate found that 85 % of the homes sold to Black

borrowers in neighborhoods experiencing “white flight” utilized contracts for deed to buy the

30 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

same homes that fleeing white families had purchased with mainstream mortgages.

111

111

Emily Badger, Why a housing scheme founded in racism is making a resurgence today, Chi. Trib. (June 10, 2018),

https://www.chicagotribune.com/2016/05/16/why-a-housing-scheme-founded-in-racism-is-making-a-resurgence-

today/; Rebecca Burns, The infamous practice of contract selling is back in Chicago, Chicago Reader (Mar. 1,

2017), https://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/the-infamous-practice-of-contract-selling-is-back-in-chicago;

Hirsch, supra note 40.

Likewise,

a study conducted by the Chicago Commission on Human Relations of one square block of the

city found that between 1953 and 1961, a total 29 parcels changed ownership. Of the 29

properties, 24 were purchased with contracts for deed. The study found that “[m]any of the

interviewed contract purchasers conveyed the impression that the installment contract was the

only means by which Negro families in Chicago could acquire property.”

112

112

Id.

Despite the oppressive financial terms of the contracts for deed, Black borrowers fought back

against the predatory practices. A group of Black homebuyers who purchased homes using

contracts for deed in Chicago formed the Contract Buyers League. The League’s goal was “to

stop exploitative contract sales, renegotiate their existing contracts, and open new lines of credit

to black home borrowers.”

113

113

Satter, supra note 42.

Although redlining was legally outlawed in 1968 by the Fair

Housing Act, the practice persists.

114

114

Coates supra note 32. See e.g., CFPB, DOJ Order Trident Mortgage Company to Pay More Than $22 Million for

Deliberate Discrimination Against Minority Families (July 27, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-

us/newsroom/cfpb-doj-order-trident-mortgage-company-to-pay-more-than-22-million-for-deliberate-

discrimination-against-minority-families/.